“We live in a democracy” – Can you show me the evidence for that?

Parliament has become unrepresentative of the diversity of views in Britain, and this drives our wider political and economic crisis as Parliament represents not the people, but a narrow group of economic interests. This is not a flaw or an oversight, it is by design – the result of decisions taken progressively over the last fifty years. This infographic uses elections data from the last century to show the reasons why.

How often have you heard the media talk about Keir Starmer’s ‘historic landslide’ at the last election in 2024? Or that Starmer’s convincing win shows ‘The Left’ has failed. Or that a majority of citizens vote for the Government of the day, or for policies like Brexit?

Our political system repeats demonstrably false messages to ensure that a ‘democratic majority’ is not represented in Parliament. From the way we vote, to the way the super-rich give political donations, the two dominant parties (and the Westminster lobbyists they have close links to) work to preserve their hold over the state, and the political power this creates, to serve the economic interests which fund UK political parties.

Votes & Constituencies

Parties win by winning the most constituencies, not the largest share of the national vote. Electors vote for candidates in their local constituency. There are currently 650 constituencies with an average of 74,000 voters in each.

The ‘modern’ Parliamentary system began in 1832: 658 Members of Parliament (MPs) were elected in that year to serve a population of 24 million; but as only around 650,000 people (3%) were allowed to vote there was one MP for every 988 electors.

Everyone in Britain – men and women, rich and poor – were given the vote equally in 1928. At the General Election in 1929 around 30 million could vote for 615 MPs – one MP for every 48,000 electors. At the last election in 2024 just over 48 million people could vote for 650 MPs – one MP for each 74,000 electors.

Smaller constituencies give more representative results: Constituencies can more closely fit settlement sizes, geographical matching Britain’s differing economic and social landscape. Having less MPs than almost two centuries ago makes them more distant from daily life, and thus less representative. Even if we had just kept the ratio from 1929, there would now be 964 MPs.

The major political parties keep the MP numbers small not because of the rising costs of democracy, but due to the control it gives them: MPs wishing to have a political career must get one of the one-hundred-and-fifty or so ministerial or committee jobs inside Parliament; and to get those jobs the MP must win the patronage of their party, not their electors. If there were more MPs, this strangle-hold over their allegiance would not be possible.

‘First-Past-The-Post’

Many blame the voting system for our woes. How often have you heard, ‘if only we had proportional representation Parliament would be more representative’. Again, this is only theoretical, and there is no evidence it would solve current political failures.

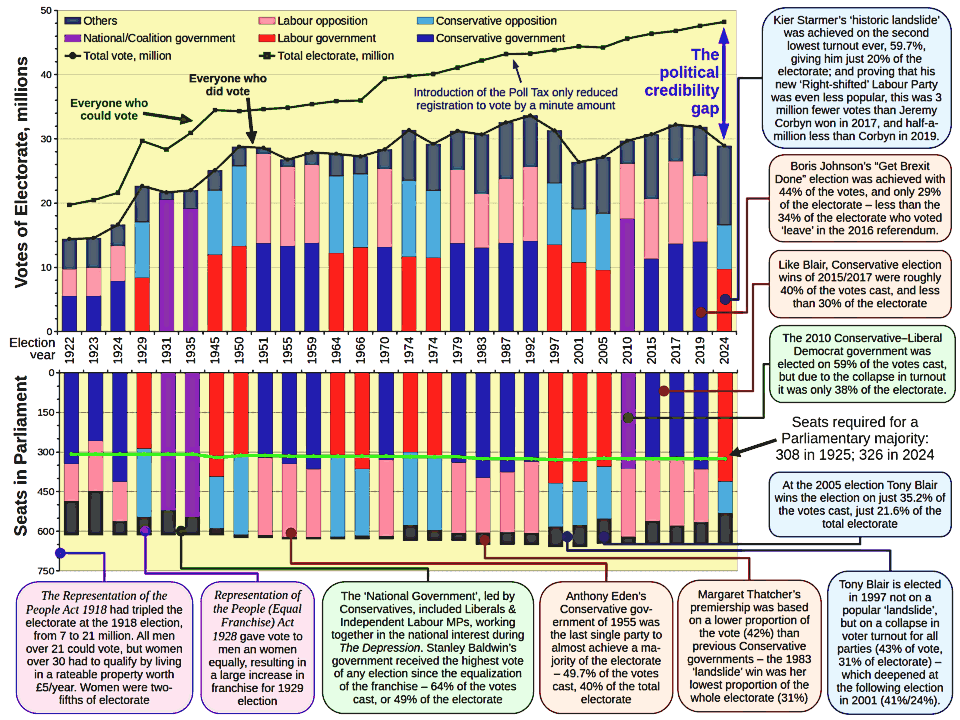

The chart above shows the results of UK General Elections from 1922. Why 1922? It shows the pattern of change since everyone got the vote in 1928.

The upper chart shows votes cast for the main parties. The ‘first-past-the-post’ (FPTP) system works well when there are only two parties. It falls apart when the ‘big two’ get less than 90% of the vote.

It’s FPTP that has preserved the two big parties for so long: To get a majority only a broad-based political block can win enough votes, which is done by polarizing and dividing the public with simple, ‘lowest common denominator’ policies.

Look carefully: The higher the ‘other’ vote, the more unpredictable the translation of vote to seats. ‘Proportional representation’ (PR) solves this by allocating seats according to the votes cast for each party – and having one or more ‘preference votes’ allows the outcome to better match people’s expectations.

The lower chart shows the seats won by each party at an election. The green line shows the number of seats required for a majority: Note how finely balanced the share between the two large parties is. There need only be a swing of a few percent to shift who is in power.

British parties have resisted PR as it would negate their historic domination. There would no longer be a need for large, broad-based parties to win a total majority. Instead coalitions would share that power, and maintaining a coalition often redistributes power to minority issues or groups. That restricts the ability of economic & corporate lobbies to deal with the large, centralized party machines behind closed doors.

The real limitation with PR, however, is what if people still choose not to vote?

Voting by Force

The two lines in the upper chart show the size of the electorate, and the numbers who actually voted at elections. Since the 1960s these lines have diverged as ever-more people have disengaged from politics and do not vote. Those most likely not to vote are the greatest ‘losers’ under the Neoliberal economic doctrine that has dominated British politics since the mid-1970s.

The last Government to be win a majority of the electorate was in 1955. Kier Starmer’s ‘landslide’ was won with only one-third of the votes cast; and as only 59.7% voted, that means just one-fifth of the whole electorate actually voted for Starmer.

As a result low turnout there calls for compulsory voting: If you do not vote, you get fined! Yet if there is no party a person can vote for, as no party truly represents them, forcing them to vote is simply a form of political oppression.

At present – for a variety of reasons – there may be somewhere between 5 million and 8 million adults not registered to vote. Compulsory voting is only likely to make this figure worse.

What Comes Next?

The 2024 election was the most expensive ever at £23 million; beating the record set in 2019 of £16.4 million. In 2024 parties received donations worth £100 million. Super-rich donors mean that parties no longer need the income that was traditionally raised by cultivating mass public support.

The next election must take place before 15th August 2029. Though 16/17 years-olds may get the vote, this doesn’t change the fundamental problem: British politics represents the interests of an affluent minority. It is this political disconnect that alienates the public, driving them to ‘populist’ parties funded, ironically, by foreign billionaires.

The problem is not just voting or representation: British politics now serves an increasingly hostile ideological minority, hell-bent on preserving the economic inequality which made them super-rich. Where no party will offer an alternative to this, by withdrawing our vote we not only oppose, we also delegitimize the harmful and divisive choices being forced upon us by our national political culture.

We need organize for localized direct democracy. To do that we must first explain to our own communities why the current system not only fails them, but why the stories they are told about that system are misleading.