‘WEIRD’, A Free Range Journal – Issue No.4, Midsummer 2021:

Thank you for calling UNTECH SUPPORT...

For a problem with technology, press 1; if this is not the future you ordered, press 2; for any other enquiries press 3 and listen to lo-fi music ´til your soul atrophies, your will to live dies, and you finally become completely desensitized to the pointlessness of consumerism.

Download this edition

1A4 PDF – for printing at A4 single- or double-sided; or

2A3 PDF – for printing landscape A3 double-sided to create a folded/stapled brochure.

‘WEIRD’ is designed to print at A4, but will reduce to A5 and be about the same size as small newsprint. The A3 PDF will scale for double-sided A4 landscape

Issue No.4 Contents:

- Introduction – ‘Untech Support’

- This tortuous pathway of disengagement, ‘untechnical support’, is a process of liberation through basic re-skilling. That’s not just about learning practical skills again; it is about building confidence in a person’s own power to discern what is right for them.

- History file – ‘Tools for Conviviality’

- Published by Ivan Illich in 1973, ‘Tools for Conviviality’ is a book on human society, the growth of sophisticated technologies, and the ecological crisis.

- Are You ‘WEIRD?’ – The answer may surprise you!

- The technocracy behind the networked world is disconnected from reality.

- We need a mass ‘uneconomic consumption’ movement

- We are told to measure ourselves by economic factors. Is the fastest route to change to opt out of that delusion?

- Couch to 5 nights camping?

- The only cheap, available space for anyone to learn the skills of simple living is ‘the outdoors’ – and the Whitehall government is trying to criminalise that.

- Marketing as a form of psychological abuse

- How advertizing & marketing morphed into ‘strategic communications’, and became organized corporate ‘mass abuse’.

- Wild tea making and the revolt against the machine

- Having the ability to go out and brew a bowl of rosehip tea on a hill is a gateway towards a lifestyle revolution.

- Numerical Ramblings – ‘Why own-grown potatoes are better energy storage devices than lithium-ion batteries’

- People obsess about electricity-producing technologies. Seldom do they think about the potential of something more hum-drum, like their food.

Introduction – ‘Untech Support’

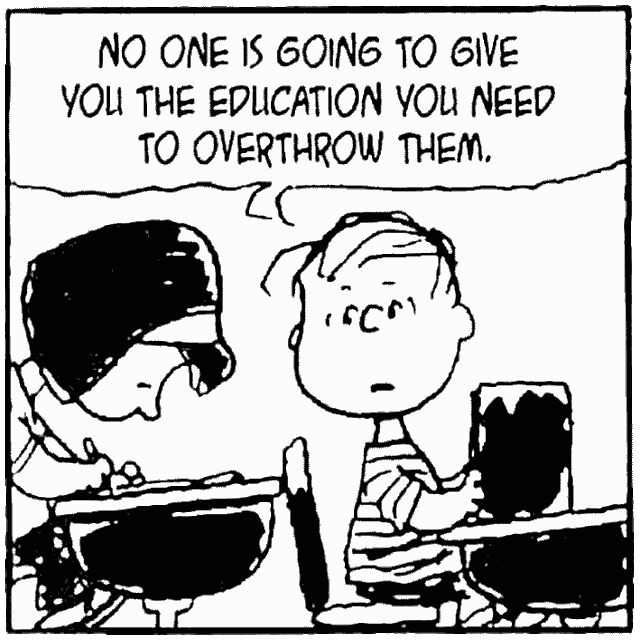

People often require help with technology. They do not understand how it works, and the gadget’s instructions are insufficient to help them do so. More commonly these days, as technology becomes ‘networked’ (we will not use the word ‘smart’ since it is an oxymoron), is that this ‘support’ is actually part of the system of dataveillance, data harvesting, and digital manipulation – synchronized with the person’s operation of the gadget.

Worse, creeping automation means, from phoning the council to a shop check-out, we are forced to use technologies that replace human interaction. You can refuse to do this, but traditional options for human interaction are slowly being put out of business as competing services automate.

OK. What if we just, “turn it off”? Cut our technological ties, and regain our basic animal freedoms, by ‘doing without’ the functions of the gadget?

It isn’t that easy. These days gadgets are tied to a person’s lifestyle: Economically via contracts, or need to do have a job; and socially, through the personal networks or identification a person has with use of the ‘thing’.

It can’t easily be ‘turned off’.

It is seldom considered that, once technology has hold of our lifestyle, people need help to ‘uninstall’ it; to find the solutions to their reliance on systems that are innately de-skilling. These processes are not the same:

The engagement process, ‘technical support’, is fundamentally exploitative. It seeks to bend a person’s routine to fit the expectations of the system’s designers – who set what the choices or options should be. The loss of skills, and the ceding of ‘choice’ to technology, makes ‘switching off’ a difficult transition to make.

This tortuous pathway of disengagement, ‘untechnical support’, is a process of liberation through basic re-skilling. That’s not just about learning practical skills again; it is about building confidence in a person’s own power to discern what is right for them, and what it is they want from their life. They must decide the values that govern their general lifestyle, and daily choices, then ‘live’ that lifestyle.

“We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning, then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man.”

C.S Lewis, ‘We Have Cause to Be Uneasy’ (1952)

It is the ‘discernment’ dimension that technology – from social media news feeds to satnavs – seeks to manipulate. It’s not simply that ‘limbic capitalism’ tries to warp your perceptions, to see the world one way rather than another. By making you doubt your own ability to choose, or making you divest that power to some on-line system, modern networked technology seizes your ability to decide your economic and social priorities – to serve its designer’s priorities instead.

In ‘WEIRD No.4’ we will explore the notion of ‘untech support’, as the first steps toward considering something more ‘practical’ once the world has sobered up after the Covid spree. The articles chosen for this edition question not so much technology, but rather people’s choices for what they believe is required for a ‘good’ life.

History file – ‘Tools for Conviviality’

Published by Ivan Illich in 1973, ‘Tools for Conviviality’ is a book on human society, the growth of sophisticated technologies, and the ecological crisis. It summed up the academic debate on ‘technics’ during the 1950s and 1960s, and brought it into the debate on global ecology in the 1970s. If you closely read the text you will see just how insightful it was – compared to the debates over similar issues today. The text below has been edited to reduce its length. The full book can be bought in bookshops, and is available free on-line.

“If within the very near future man cannot set limits to the interference of his tools with the environment and practice effective birth control, the next generations will experience the gruesome apocalypse predicted by many ecologists. Faced with these impending disasters, society can stand in wait of survival within limits set and enforced by bureaucratic dictatorship. Or it can engage in a political process by the use of legal and political procedures…

The bureaucratic management of human survival is unacceptable on both ethical and political grounds… This does not, of course, mean that a majority might not at first submit to it…

Myths and Majorities

The ultimate obstacle to the restructuring of society is not the lack of information about which limits are needed, nor the lack of people who would accept them if they became inevitable, but the power of political myths.

Almost everyone in rich societies is a destructive consumer. Almost everyone is, in some way, engaged in aggression against the milieu. Destructive consumers constitute a numerical majority. Myth transforms them into a political one. Numerical majorities come to form a mythical voting bloc on a non-existent issue; “they” are invoked as the unbeatable guardians of vested interest in growth. This mythical majority paralyses political action.

At closer inspection, “they” are a number of reasonable individuals. One is an ecologist who takes a jet plane to a conference on protecting the environment from further pollution. Another is an economist who knows that growing efficiency renders work increasingly scarce; he tries to create new sources of employment. Neither of them has the same interests as the slum-dweller in Detroit who purchases his colour TV on {credit}. The three belong no more to a voting bloc that will defend growth than clerks, repairmen, and salesmen are somehow politically homogenized because each fears for his job, needs a car, and wants medicine for his children.

There can be no such thing as a majority opposed to an issue that has not arisen.

A majority agitating for limits to growth is as ludicrous a concept as one demanding growth at all cost. Majorities are not created by shared ideologies. They develop out of enlightened self-interest. The most that even the best of ideologies can do is interpret this interest.

The stance each man or woman takes when a social problem becomes an overwhelming threat depends on two factors: the first is how a smouldering conflict erupts into a political issue demanding attention and partisan action; the second is the existence of new elites which can provide an interpretative framework for new − and hitherto unexpected − alignments of interest.

From Breakdown to Chaos

I can only conjecture on how the breakdown of industrial society will ultimately become a critical issue…

I believe that growth will grind to a halt. The total collapse of the industrial monopoly on production will be the result of synergy in the failure of the multiple systems that fed its expansion. This expansion is maintained by the illusion that careful systems engineering can stabilize and harmonize present growth, while in fact it pushes all institutions simultaneously toward their second watershed.

Almost overnight people will lose confidence not only in the major institutions but also in the miracle prescriptions of the would-be crisis managers. The ability of present institutions to define values such as education, health, welfare, transportation, or news will suddenly be extinguished because it will be recognized as an illusion…

People will suddenly find obvious what is now evident to only a few: that the organization of the entire economy toward the “better” life has become the major enemy of the good life. Like other widely shared insights, this one will have the potential of turning public imagination inside out…

People who invoke the spectre of a hopelessly growth-oriented majority seem incapable of envisaging political behaviour in a crash. Business ceases to be as usual when the populace loses confidence in industrial productivity, and not just in paper currency.

It is still possible to face the breakdown of each of our various systems in a separate perspective. No remedy seems to work, but we can still find resources to support every remedy proposed.

Governments think they can deal with the breakdown of utilities, the disruption of the educational system, intolerable transportation, the chaos of the judicial process, the violent disaffection of the young. Each is dealt with as a separate phenomenon, each is explained by a different report, each calls for a new tax and a new program.

Squabbles about alternative remedies give credibility to both: free schools vs. public schools double the demand for education; satellite cities vs. monorails for commuters make the growth of cities seem inexorable; higher professional standards in medicine vs. more paramedical professions further aggrandize the health professions.

Since each of the proposed remedies appeals to some, the usual solution is an attempt to try both. The result is a further effort to make the pie grow, and to forget that it is pie in the sky…

We still have a chance to understand the causes of the coming crisis, and to prepare for it. If we are to anticipate its effects, we must investigate how sudden change can bring about the emergence into power of previously submerged social groups.

It is not calamity as such that creates these groups; it is much less calamity that brings about their emergence; but calamity weakens the prevailing powers which have excluded the submerged from participation in the social process. It is the power of surprise that weakens control, that shakes up the established controllers, and brings to the top those people who have not lost their bearings.

When controls are weakened, those accustomed to control must seek new allies. In the weakened economic-industrial state of the Great Depression, the establishment could not do without organized labour, so organized labour got its share of power within the structure.

Insight into Crisis

Forces tending to limit production are already at work within society… They form no constituency, but they are spokesmen for a majority of which everyone is a potential member. The more unexpectedly the crisis comes, the more suddenly their desires can turn into a program. But the ability to direct events at that moment depends on how well these minorities grasp the profound nature of the crisis, and know how to state it in effective language: to declare what they want, what they can do, and what they do not need…

Further growth must lead to a multiple catastrophe. That people would accept multiple limits to growth without catastrophe seems highly improbable. The inevitable catastrophic event could be either a crisis in civilization or its end…

Sacrifice must be shown as the inevitable price for different groups of people to get what they want − or at least to be liberated from what has become intolerable. But beyond using words to describe the limits as both necessary and appealing, the leadership of these groups must be prepared to use a social tool that is fit to ordain what is good enough for all…

I have already argued that such a tool can only be the formal structure of politics and law. At the moment of the crash which is industrial rather than simply financial, the transformation of catastrophe into crisis depends on the confidence an emerging group of clear-thinking and feeling people can inspire in their peers. They must then argue that the transition to a convivial society can be, and must be, the result of conscious use of disciplined procedure that recognizes the legitimacy of conflicting interests, the historical precedent out of which the conflict arose, and the necessity of abiding by the decision of peers…

Sudden Change

When I speak about emerging interest groups and their preparation, I am not speaking of action groups, or of a church, or of new kinds of experts. I am above all not speaking about one political party which could assume power at a moment of crisis. Management of the crisis would make catastrophe irreversible… But the crisis I have described as imminent is not a crisis within industrial society, but a crisis of the industrial mode of production itself. The crisis I have described confronts people with a choice between convivial tools and being crushed by machines…

I am also not speaking about a majority opposed to growth on some abstract principles. Such a majority is unfeasible. A well-organized elite, vocally promulgating an anti-growth orthodoxy, is indeed conceivable. It is probably now forming. But such a programmatic anti-growth elite would be highly undesirable.

By pushing people to accept limits to industrial output without questioning the basic industrial structure of modern society, it would inevitably provide more power to the growth-optimizing bureaucrats and become their pawn…

The proponents of a bounded society have no need to put together some kind of majority. A voting majority in a democracy is not motivated by the explicit commitment of all its members to some specific ideology or to some particular value. A voting majority in favour of a specific institutional limitation would have to be composed of very disparate elements: those seriously aggrieved by some aspect of overproduction, those who do not profit from it, and those who may have objections to the over-all organization of society − but not directly to the specific limit being set.

A majority vote to limit one major institution tends to be conservative when business is as usual. But a majority can have the contrary effect in a crisis which affects society on a deeper level. The joint arrival of several institutions at their second watershed is the beginning of such a crisis.

The crash that will follow must make it clear that industrial society as such − and not just its separate institutions − has outgrown the range of its effectiveness. The nation-state has become so powerful that it cannot perform its stated functions…

As a total crisis approaches, it becomes more obvious that the nation-state has grown into the holding corporation for a multiplicity of self-serving tools, and the political party into an instrument to organize stockholders for the occasional election of boards and presidents. In this situation, parties support each voter’s right to claim higher levels of consumption and to enforce thereby higher levels of industrial consumption…

A general crisis opens the way to social reconstruction. The loss of legitimacy of the state as a holding corporation does not destroy, but reasserts, the need for constitutional procedure. The loss of confidence in parties that have become stockholders’ factions brings out the importance of adversary procedures in politics. A loss of credibility of opposing claims for more individual consumption only highlights the importance of the use of adversary procedures when the issue to be decided upon is the reconciliation of opposing sets of society-wide limitations. The same general crisis that could easily lead to one-man rule, expert government, and ideological orthodoxy is also the great opportunity to reconstruct a political process in which all participate.

The structures of political and legal procedures are integral to one another. Both shape and express the structure of freedom in history. If this is recognized, the framework of due procedure can be used as the most dramatic, symbolic, and convivial tool in the political area…

Reconstruction for poor countries means adopting a set of negative design criteria within which their tools are kept, in order to advance directly into a post-industrial era of conviviality. The limits to choose are of the same order as those which hyper-industrialized countries will have to adopt for the sake of survival and at the cost of their vested interest…

Defence of conviviality is possible only if undertaken by the people with tools they control. Imperialist mercenaries can poison or maim but never conquer a people who have chosen to set boundaries to their tools for the sake of conviviality.”

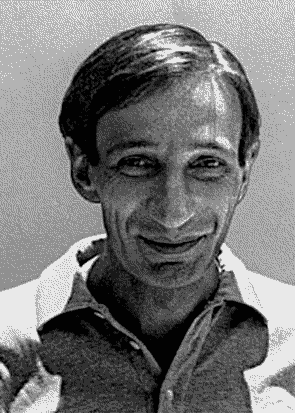

Ivan Illich (4th September 1926 – 2nd December 2002), Theologian, philosopher, and social critic.

Are You ‘WEIRD?’ – The answer may surprise you!

The networked world, created to give everyone the power of mass communication, has become disconnected from reality; that’s not so much the fault of the dumb, digital network, but of the minds that manipulate it.

We have been asked why we chose to call this newsletter, ‘WEIRD’? Why do we use a “negative” label to define our work? The answer is really two ways of expressing the same perspective on the modern world – and how that world seeks to define a role for us which we reject.

One of the founding magazines of digital culture, first published in 1993, was ‘Wired’. Certainly in the 1990s, Wired’s techno-utopian content fed into the rising economic and political power of Silicon Valley, and of the (then small) companies which were creating the new ‘digital economy’.

In one sense this newsletter represents the opposite of that viewpoint – for which you need only shift one letter in ‘wired’ to the left to express how that view is regarded by mainstream culture.

However, the practical reason for this label is the little discussed acronym that the title represents. ‘WEIRD’ first emerged as a criticism of the bias within modern psychological research, skewed by consumerism and the political values that the modern western lifestyle represents. The ‘WEIRD’ acronym labels these biases, and how they distort debates:

- ‘Western’ – a culture whose norms and values are defined by Americans and Europeans;

- ‘Educated’ – a culture that is (allegedly) refined and rational, representing the dispassionate values of modern technocracy;

- ‘Industrialized’ – a culture based on the goods created by industrialism, and the technologies which enables it;

- ‘Rich’ – a culture that represents affluent consumption, primarily of the middle class, ignoring the more challenging lifestyle of the domestically or globally poor; and

- ‘Democratic’ – a culture that professes open, meritocratic, majoritarian control, but which represents mainly the economic and political desires of a narrow highly-affluent elite.

In 2008, a study found that 96% of the participants in psychological research studies were ‘WEIRD’ – even though this group is only 12% of the global population. Often, they were students from American universities, which skewed the sample even more as only a third of US citizens go to university. Problem is, many Western governments use the results of such studies to decide educational, economic, or social policy for everyone else in society.

One less-well-used definition of ‘consumerism’ is: “The inability of a person to critically discern their needs from their wants under a systematized psychological assault on their freedom to choose.”

The five factors making up WEIRD represents a source of cognitive dissonance – a contradictory set of ideas which cause people stress and confusion when they try to understand what they are told, and what they personally experience or feel.

For example, WEIRD people could be considered ‘rich’ in global terms. Yet in their own nation they are subject to economic pressures as a result of debt, or high living costs that lower their perceived standard of living. Likewise people might celebrate ‘education’, but that education may also tell them that their world is collapsing as a result of their affluent lifestyle.

The media reflects consumer values, obviously; economic values underpin their business model. But, as outlined in the previous article by Ivan Illich, that debate in-turn assumes a political constituency to support that lifestyle, when in fact no such homogeneous constituency exists. There are a diversity of reasons people might believe in economic growth, or fiat money, but that doesn’t mean they share those reasons with the people at the top making decisions about the economy.

In the absence of people being able to judge their essential needs for well-being, that debate largely takes place without any opposing point of view. That failure to challenge assumption then means, from on-line banking to on-line public services, the majority of people are forced into a certain ways of living, even if it doesn’t represent the best or most desired option for them as an individual.

The rise of this culture has – over the last forty years – gone hand-in-hand with rising poverty and inequality in the Western states most wedded to this system of values; like Britain, the USA, or Australia. That is because the decisions taken by allegedly ‘democratic’ states do not reflect the interests of all citizens, only a socially narrow, affluent minority.

For example, in Britain in March 2020, the government created a legal ‘right’ to a broadband connection with a download speed of 10 megabits-per-second and an upload speed of 1Mbit/s. For many years, though, the government has refused to grant a legal right to food, even thought it's part of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. The Trussell Trust opened its first food bank in 1999; today it has over 1,300, and nationally it is estimated 2.5 million people rely on food banks...

“Have you ever considered an alternative energy supplier?”

“No, I’m quite happy with food”

Gary Delaney

You’ve a right to stream cookery shows in HD, but don’t expect to have any food if you can’t afford it.

It is not possible to talk about the ecological crisis without seeing how WEIRD values restrict that debate in politics, academia, and the media. By excluding ideas which challenge the that culture, society: Routinely ignores, or censors issues or research critical of affluence and consumption; while giving undue weight to other, often assumed ‘facts’ about the world which reinforce that culture of affluence and consumption.

We’ve also been asked why this publication is only available as a PDF on-line; and why we ask that people print and copy to share ‘physically’ instead of sharing ‘electronically’. [Note, 2025: Due to repeated demands there is now an on-line copy, but we far prefer that people print and share off-line from the PDFs]

Though scientific and political debate is WEIRD, research suggests that what happens in the on-line world is WEIRD-er! For example, it’s been known for some time that on-line surveys produce biased results; and these surveys can be easily made to produce even more biased results by using on-line ‘filter bubbles’ to ‘self-select’ who responds. One recent German study found that national policies to response to Covid, based on results from on-line surveys, were skewed because only those who believed in or trusted the government were likely to reply – which gave a false idea for how many would carry out the measures suggested.

The on-line world is WEIRD-er because it is being deliberately manipulated by certain agencies for their own ends. That happens at all levels, quite often invisibly:

Search engines use algorithms to show the results people ‘want to see’. At the same time they try to filter or censor certain types of content – result, people don’t get what they asked for.

Social media platforms use algorithms not only to ‘show people what they want’, but also to show information that causes strong emotional reactions in the user. This so-called ‘microtargeting’ – using data on the individual to precisely target their preferences, or weaknesses – is increasingly what platforms are paid for.

Underlying the growth of social media – and the political panic over (alleged) ‘fake news’ – the generally WEIRD nature of English language content also skews these results further. Even beyond that, though, platforms skew results in some very strange directions.

One example is the ‘Alt-Right rabbit hole’, where the programmed trend towards ‘click-bait’ drives people towards right-wing sites. For example, an internal Facebook report from 2016 stated that almost two-thirds of people joining extreme-right groups did so because the site’s algorithms had recommended those pages. Left-wing groups don’t get the same preferential treatment!

Platforms also downplay left-wing and ecologically conscious content. Most corporate media promotes the opposite viewpoint, so ‘dissent’ is not rated highly in searches due to the mainstream media’s WEIRD centre-right bias.

Overall the bulk of search results are skewed by the amount of pro-economic, pro-consumption corporate-sponsored on-line content. Unless the search phrase, or the social media page narrowly focusses on just that subject – and excludes greenwash and click-bait designed to mislead – it’s less likely to rate highly in the results.

We can also replace the ‘W’ of the acronym with ‘White’ (and male), since on-line and digital technology systematically discriminates against women, and especially people of colour – a trend called ‘coded bias’.

These biases are hard-coded into the system. In part, it’s a result of the bias of its WEIRD creators. E.g., in 2016, Microsoft launched an ‘intelligent’ AI-based chatbot called ‘Tay’ on Twitter. The system was considered revolutionary, as it used language analysis to frame its responses according to other on-line discussions. After 24-hours they had to switch it off when it started spouting racist, genocidal, and misogynistic messages to its followers.

In the 1980s, digital utopians believed the Internet’s non-hierachical structure would allow ‘ordinary’ people to have equal access to the media environment. Contrary to that utopian ideal, the technology could not change the fundamentally WEIRD nature of those building the system. Branding and content syndication gave platforms a monopoly, creating an inevitable nexus of influence, reasserting an algorithmically-generated hierarchy on the ‘Net.

The only people who correctly guessed the outcome were the cyberpunk authors!

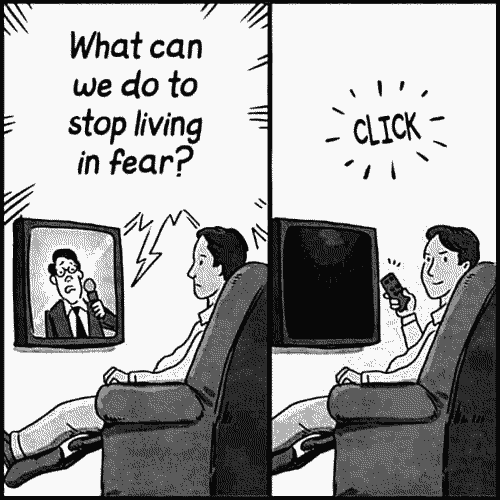

People need to be ‘clicking’ more – and what they need to be clicking is the ‘off’ switch.

There’s a simple way to get around WEIRD, and the on-line media cesspool of bias: ‘Do-It-Yourself’, off-line. That is why our bias is towards off-line reading, and why our content seeks to challenge the economic and political foundations of WEIRD culture.

We need a mass ‘uneconomic consumption’ movement

We are told to focus our entire lives upon economic factors. Could it be that the fastest route to true change is to opt out of that consensual delusion, with a bit of old fashioned/punk D.I.Y?

Just about every plan to ‘end poverty’, or ‘save the planet’, or address corporate excess, takes the modern lifestyle as an invariant factor: They will not question affluent lifestyles as part of their response; nor the toll that meeting those expectations takes upon both humans and the planet.

Too many people believe they’re changing the world, but are in fact, through their blind allegiance to the economics of affluence, reinforcing the systems which divide it. The question we need to ask is, “how exactly do you escape from the ‘suicide cult’ of modern society?”

At the end of the main news we receive our daily secular blessing: “The Dow is up; London is down; interest rates are low”. Then some politician tells you that they’re doing everything for ‘jobs’ and ‘growth’. And binding it all together, from the mobile apps. exploiting Deliveroo riders to the algorithms monetizing people’s every on-line click, the structures surrounding people’s routine lives press-gang them into consuming like a ‘normal’ member of society.

“Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfactions, our ego satisfactions, in consumption. The measure of social status, of social acceptance, of prestige, is now to be found in our consumptive patterns. The very meaning and significance of our lives today expressed in consumptive terms. The greater the pressures upon the individual to conform to safe and accepted social standards, the more does he tend to express his aspirations and his individuality in terms of what he wears, drives, eats, his home, his car, his pattern of food serving, his hobbies... We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing pace. We need to have people eat, drink, dress, ride, live, with ever more complicated and, therefore, constantly more expensive consumption.”

Victor Lebow, ‘Price Competition in 1955’, Journal of Retailing, Spring 1955

This system did not arise accidentally; but neither was it created by some shadowy elite sitting in a global control centre. It arose over the last century as a few influential thinkers steered corporate and government policy-makers towards making economics and consumerism a ‘secular cult’. For example, the early promoter of mass consumerism, Victor Lebow (see right).

What if the only way out of that economic and technological ‘trap’ is not to ‘reform’, but to deliberately seek to break it?; to hasten its inevitable collapse before it takes the entire world ecosystem with it?

As Ivan Illich outlined earlier, the idea of a mass movement to stop consumption is bound to fail. What we must do instead is exclude those values from our lives; and through that process, find like-minded people who would like to work to do the same. Then, as Illich outlines, when things get bad, that group can be the inspiration for those willing to listen to ‘other options’.

If this system was made incrementally, then we can break it incrementally – by defying those everyday pressures on us to consume.

“On y’er bike!”

A fake article was drifting around social media, attributed to a banker. Even when it was known to be a spoof it kept circulating, as people implicitly felt it to be true even though it was technically a lie: Bicyclists are a menace to the global economy!

For many this would be a big ask; but that’s the point. Society traps people into one ‘acceptable’ activity rather than another; precisely because the economic lobby – like bankers – consider the option which creates the most spending and consumption to be the best one.

What if you stopped using a car, and went everywhere by bike? (or for long rides, public transport)

It’s easy to see why many people choosing to take that option would be a disaster for the economy:

According to the Office for National Statistics, about a seventh (~14%) of household income is spent on transport. Averaged over each week, a third of that average cost is buying new cars, and another two-fifths is the cost of running the vehicle. In contrast 0.3% of transport spending is buying bicycles, and 0.1% on running them.

A person who can get around on a bike need not buy a car. More importantly, by not borrowing money to buy a car, it denies the ability of banks to create yet more debt (and profit) in the economy. Non-car drivers don’t pay insurance, don't need to buy fuel, and don’t have to fork out for increasingly expensive maintenance costs.

~£80 billion a year is spent by households on cars, but only ~£30 billion on public transport. Proportionately not having a car, and going by bike, denies the economy a large wad of cash!

Right now one of the ways to give the police the legal authority to demand your name and address is to drive a car. Don’t drive a car, and they need a reasonable excuse to even talk to you.

Of course, it takes time to use a bike properly because you have to get fit. Then you have the problem that increasing your cardio-vascular fitness will make you more healthy in general, meaning the NHS won’t spend as much on medical services. You also won’t be buying lots of drugs and treatments for the symptoms of ill-health that arise with a sedentary lifestyle.

In summary: Bike riders are a menace to economic activity and the growth of the economy! Is it any wonder all governments refuse to spend any significant amounts of public transport, and especially cycling infrastructure? The collapse of private car use would endanger economic growth.

Of course, bicyclists must buy a bike and spares. The most threatening type of anarchist are those who choose to walk everywhere!

“It's good to talk”

Do not use a smartphone: Forget the micro-management of your life with apps. and platforms. Forget the ecological impacts of mining the rare metals, and the energy required to run the system. Ignore the controversy over the health effects. Just focus on the bigger economic picture.

Twenty years ago households spent 2½% of income on ‘communications’. Today it’s over 3½%. People pay up to twice the amount to make a call now as twenty years ago. In 2020, UK households spent £40 million/week buying mobile phones, and £200 million/week using them.

Now think of the other things that are happening around you.

Why are local banks closing? It’s the effect of ‘financial tech.’ (see WEIRD No.1). The pioneers of on-line banking cut costs for the affluent to manage their money from mobile phones. High Street banks then had to follow the trend or lose their most lucrative customers. Result: As more banked on-line, less-lucrative customers had to go on-line as expensive to run local banks were shut, and thousands of staff lost their jobs to automation and cashless payments.

The real ‘gig’ for the future of finance technologies is monetizing your habits. As more transactions go on-line, you tell the banks more about yourself. Combined with the location data from the mobile phone, that can be used as a powerful marketing tool to drive people into impulse purchases.

Along with addictive drugs (from which British banks made a fortune in the 19th Century), smartphones are one of the most exploitative, manipulative devices ever created to enslave the public and take their money. Why not just use landlines?

Food for thought

‘Adding value’: From pub hospitality, to food processing, to farm diversification, is all about making people pay for ‘convenience’.

“Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what your are.”

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, ‘Physiologie du Gout’ (1826)

Before Covid, many UK consumers were spending over £2,000 a year in coffee shops; in total, £14½ billion. Even after the 2008 crash, the number of coffee shops had almost doubled before Covid hit.

A coffee farmer might get half-a-percent of the price of a cup. The franchize might only get 10%. Most of the cost – perhaps a third to two-fifths – ends up in the pocket of the retail landlords who rent the shop.

Over the last decade the sales of chilled ready meals has risen 50%, to £1.5 billion a year; still a way behind the value of frozen food sales, ~£7 billion a year.

In WEIRD No.1 we outlined, ‘the problem with frozen chips’. It’s possible to make many convenience meals more cheaply at home – and usually more healthy in terms of their nutrition too. The problem is things like oven chips, which are effectively sold at a loss because people will likely buy the over-priced piece of dead animal placed next to them in the aisle.

The exception would be to grow your own potatoes. Own-made oven chips would then be cheaper than the shop’s ‘loss leader’ option. This is why, especially in relation to food, we can’t ignore the issue of English and Welsh land rights (the Scots are way ahead on this issue).

The economics of town centres – from rising rents to closing public toilets – drove people into expensive coffee shops; sucking money from local economies to a few retail landlords. If many more people had affordable access to land, it could be the basis to re-establish local trade and economies in the most essential commodity – food.

Until then, why not cut-out the middle man and ‘do-it-yourself’? – take your own-made food instead of buying from expensive shops.

Conscious versus unconscious consumers

Let’s get one thing straight: In Britain today – where so many are denied the ability to live cheaply on and make their own lifestyle from living on the land – you must consume or you will die.

Preventing people having autonomy, since the beginning of industrialization & urbanism 300 years ago, has been the British establishment’s method for controlling the public; forcing them to use ‘their’ economic system. You shouldn’t feel bad about it; it just ‘is’.

You do not have the freedom to refuse all participation. As Victor Lebow outlines, what the system seeks to do is make consumption unconscious: So effortless and inconsequential it becomes, as he states, a ‘ritual’. That process truly began with the liberalization of consumer credit in the 1960s, but the recent shift to on-line, ‘instant gratification’ shopping has put that process on steroids.

What you do have is the freedom to choose is the ‘mode’, or the standards for your participation. That does not mean avoiding consumption – as the tokenistic, ‘Buy Nothing Day’ advocates talk of. What it means is ‘consciously’ consuming only those things which are essential for your needs, and rejecting the rest; and doing so on terms that serve your well-being, not ‘their’ power and profit. The means to do that is to make your ‘rituals’ to be things that are bad for their economy; those thing which stop growth.

That’s what we mean by a movement for ‘uneconomic consumption’. It embodies the ideas of buying less, or repairing more, yes; but that’s framed by a deliberate intent to buy things in a way which: Minimizes the burden of costs to the individual, to create greater economic freedom by making life less money-dependent; while at the same time, denying revenue & economic influence to those who run this political Ponzi-scheme.

Couch to 5 nights camping?

In England & Wales the only cheap, easily available space for anyone to learn the skills of simple living is ‘the outdoors’; and right now the Whitehall government is trying to criminalize ‘free camping’ in the open countryside.

On-line communities are a trap. Yes, they have value as a communications space; but if you want to actually ‘create’ a physical alternative community then you must do that off-line – in the ‘real world’.

If you’re trying to create a community, to learn how to live beyond the coming collapse of consumerism, it’s even harder. For centuries the English state has frowned upon that kind of activity; and from The Diggers to peace convoys, has sought to exterminate them.

Why ‘Couch to Five Nights’? – A brief description of the project

If you are physically able, being outdoors is the cheapest, simplest way to learn basic skills for living, and to improve your physical strengths to live with less. It’s also important to find a group to do these activities with.

That process begins by getting away from the screen/off the couch and going outside. You might find friends on-line, but you need to get outdoors together ‘in real life’ to get the experience(s) required.

The first part of the project will focus on basic outdoor skills and information. By necessity, the ‘day out’ skills will include respectfully using camp-fires to cook on instead of fossil-fuelled stoves.

After that, when you are comfortable being outdoors, the next step is ‘static’ camping – where you go to a location and stay for a night or two, perhaps using local shops and services to support that. That’s because it requires a minimum of equipment and skills.

Ultimately the aim of this project is to encourage people to go fully ‘off the map’ – spending three to five night outdoors, self-contained, reliant only on what they can take. That could be static, in one location; though our particular preference is to travel taking a minimal level of equipment with you – either in a backpack or on a bicycle.

The specifically new part of of this project, though, is the inclusion of land rights issues. That begins with learning to cook outdoors on a fire; which currently the government has a bit of a downer on.

The most controversial element will be camping outdoors on open land – for which we will be developing a legal resource to challenge the law.

The project aims to challenge the legitimacy of the English state – in contrast to Scotland – in preventing people from accessing the land; and maintaining a historic privilege of land ownership for a few.

We must ‘rewild the people’: That begins by giving access to the land to learn the necessary skills to do it; and, the right to pursue a low impact lifestyle, living from the land.

To learn how to live “when the shit hits the fan” (WTSHTF) you need to escape the restraining influence modern life; to learn and practise these skills in a ‘safe’ space today, for when you’ll need to use them in earnest in the future. But where can you go to escape the temptations of technology and easy living, to experience what the it is like when those things are not easily available?

That begins by having a space where people can get together and practise the skills required as a ‘community of shared interest’. And unless you’re affluent enough to own land, for most the only space where people can meet to practise living outside of the consuming world is the outdoors.

Most ordinary people don’t have a lot of space to do that. Public spaces are becoming increasingly hostile to people meeting in groups doing anything other than a basic picnic, and most have made camping in parks unlawful.

What we have is the countryside, and our tenuous rights of access to it. Perhaps not coincidentally, the government is trying to restrict those rights even further – effectively making a more nomadic life, living permanently outdoors, a criminal offence.

“But I hate camping”

Clearly, this is a hard sell. Many people just ‘don’t do’ camping; in part because it does require effort, and a lack of luxury. That’s the whole point! What do you think ecological collapse will be like?

Many people, right now, are being forced to live like this full-time by homelessness – caused by the current economic state of things. Though most people see rough sleeping in towns an cities, there are in fact large numbers of people living in tents secluded in the countryside, or in vehicles, often still employed.

The government’s current crack-down on nomadic lifestyles is, in part, an attempt to control this unforeseen impact of their awful economic policies. It’s sad that none of the media pundits giving glowing reviews to the recent Oscar-winning film, ‘Nomadland’, chose to reflect that our government is trying to criminalize that lifestyle here.

Now think: What if that were you? What if you were forced out of your permanent home? How would you live?

Resurrecting an old campaign

In 2006, The Free Range Network began a project: ‘The Great Outdoors’. It worked really well at first; teaching low impact living with weekends camping outdoors. Then, after the 2008 crash, the weekends sort-of tailed off. After the crash people didn’t need to ‘learn’ how to have less; they were made to do it by circumstance.

“‘Sustainability’ is, as far as I can see, a project designed to keep this culture – this lifestyle – afloat”

Paul Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain Project co-founder

It’s time to resurrect that project, but not as a ‘sustainable living’ action. The imperative today is to create a visible campaign for land rights in England and Wales.

Spending time learning practical skills outdoors is a way to move beyond the expectations of the modern lifestyle. Even if that does not lead to you rethinking your lifestyle in the immediate future, as the inevitable breakdown of ‘normality’ grinds inexorably forward over the next 10 to 20 years, these skills will give you options to deal with those events as they arrive.

“Rewilding the people”

A fashionable issues in ecological circles is ‘rewilding’ – giving land back to ‘animals’. Though affluent, aristocratic figures promoting this idea exclude ‘human animals’ from the scope of their thinking.

There is neither the time nor the resources to replace the energy and service from fossil fuels with renewable energy. That means, to prevent catastrophic collapse, people will be forced to consume less. If you think how politicians in the US or USA handled the Covid crisis, which had a foreseeable end, how do you think they’ll handle an ecological collapse which has no ‘end’?

This is why we must ‘rewild the people’. The most low impact, resource efficient way humans can live on the Earth is to source their essential needs directly form the land.

That, then, is the ultimate goal for this project: Teaching people basic skills to ‘reside on the land’; but ultimately, through a land rights campaign, pressuring for the dismantlement of England’s historically privileged land ownership system – enabling ordinary people to have access to a small plot to live a low impact lifestyle upon.

The current policies of successive government ensure that a future collapse of ‘modern’ society is inevitable. Their inability to recognize that failure violates any pre-existing social contract. Therefore we must agitate for the future we believe offers our greatest chance for survival.

From ‘Shiny New Objects’ to ‘Fear of Missing Out’ – Marketing as a form of psychological abuse

How advertizing & marketing morphed into ‘strategic communications’, and became organized corporate ‘mass abuse’.

In his 1957 book, ‘The Hidden Persuaders’, US journalist Vance Packard identified a number of key weaknesses in human psychology which marketing tweaks – making people buy a certain product because they believe it represents something more than it is. The book caused a sensation, and was one of the first to critically look at how market sought to manipulate people’s perceptions.

Less well know is his 1964 book, ‘The Naked Society’. It was the first to look at the use of data collection and computers to target people, not just for marketing, but also propaganda campaigns.

Almost sixty years later and what Packard talked of appears old fashioned. We have moved way beyond what he foresaw.

The early work of marketing identified trends across the whole population – as described earlier, from those ‘WEIRD’ psychological studies carried out on unwitting consumers. It then used those reactions as pressure points to sell goods. Of course, those studies generalized across the whole population, and the results were predictably hit and miss.

The latest generation of on-line surveillance seeks to identify unique individuals, then collect data about their on-line habits, as well as credit card and bank data. Then, through a system called ‘microtargeting’, that data is used to identify people who represent a particular preference. But whereas that identifiable group might once have numbered millions, today it might be just a few thousand.

In the modern world, though, that need not be to sell things.

When TransCanada planned the ‘Energy East’ pipeline across Canada they used the ‘strategic communications’ company Edelman to gather data on communities on the route. Not for publicity, but to catalogue groups or people who represented a threat to the project locally. Strategic communications is not classed as ‘marketing’. Instead its use is considered to be a form of political lobbying.

Just as the US military developed ‘signature strikes’, tracking cell phones and dropping bombs on them, the latest lucrative applications of microtargeting are ‘negative’ public relations – where a government or corporation seeks to track and neutralize opposition. Most famously, the Vote Leave campaign used the company Cambridge Analytica, and their Canadian counterpart AggregateIQ, to target people with texts and on-line propaganda to vote for Brexit.

In May 2021, the government announced a second attempt to privatize people’s medical records through ‘NHS Digital’ – previously abandoned in 2014. Major health professionals’ bodies oppose this, but it’s being pushed ahead anyway. Though it is argued the data is anonymous, it allows microtargeting of geographical areas on certain health issues – for ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ purposes.

“Economic growth may one day turn out to be a curse rather than a good, and under no conditions can it either lead into freedom or constitute a proof for its existence.”

Hannah Arendt, ‘On Revolution’ (1965)

You need to opt-out of all data collection to avoid being unwittingly pressured through microtargeting. Avoid store cards, and loyalty cards, etc. etc. There’s so much out there to read on how to protect your privacy.

Most importantly, go to your doctor’s surgery before the end of August to opt-out of the NHS sharing your medical records.

Wild tea making and the revolt against the machine

Having the ability to go out and brew a bowl of rosehip tea on a hill is a gateway towards a lifestyle revolution. It’s not the literal tea-brewing; it’s the mind-set created by undertaking such ‘uneconomic’ activities, freely, without technology.

Most ecological issues can be solved with “less”: Less consumption; less pollution; less extraction; and combining all of those, less technology.

The reality of mass consumption is that the lifestyle it supports is dependent upon the ability to consume. Losing your economic status, or if the system falls into crisis, will quickly mark the end of that lifestyle.

Why ‘anarcho-primitivism’?

The path out of technological society must rely on the tools or solutions which can work outside of that system. The only formal criticism of today’s way of life which does this is ‘anarcho-primitivism’ (or ‘A/P’) – the idea that society can be best organized along simple, low-tech., land-based lifestyles, where people have a direct connection to the land and natural systems.

Though people talk of ‘going back’ to some idealized existence, the reality is that any future without technology has to take the best of past lifestyles, and make them work within today’s resource-stripped, low-biodiversity world. That stark difference between the damaged world as it is today, and world of just a couple of centuries ago, is more of an obstacle to ‘going back’ than modern-day consumerism itself.

Unfortunately, A/P has become so ensnared by the affluent society; advocates for it are themselves deeply compromized by that system. Put “anarcho-primitivism” in a search engine and what you get is Powerpoint presentations, or earnest academics looking at utopian worlds that can’t exist today. Everything, it seems, but a workable, practical way to map a path outside of the maze of present-day technological society.

At the same time there are permaculturists, or bushcraft enthusiasts, or simple living advocates, who use techniques outside of the restrictions of ‘complex’ technology, living simply and cheaply in the process. Though their work may avoid a critical view of technology, their activities are directly relevant to finding a future plan, ‘beyond technology’.

There isn’t space here to look at the history of A/P, but it’s a subject that will be examined in future editions – alongside the practical actions that give those ideas real-world meaning today.

Every ‘ordinary’ person in the system secretly knows this; and a lot of political and media fodder, from fashion to election messages, exploit that fear to get attention. This consumption- and technology-critical argument was at the core of early environmentalism from the 1960s; but as the leaders of the environment movement sought to take ‘green’ into the political mainstream, from the late 1980s that radical core was dropped – in favour of more consumption-friendly slogans. Now anyone could be ‘green’… if they could afford to buy the right products.

Just as the pressures of consumerism made environmentalists abandon their core values, so, in the affluent states, the response of the left has been to abandon their principles too – the British Labour Party being a perfect example.

What remains of leftist politics, and anti-capitalism, has retreated to the on-line world – ensuring its digital ghettoization by the algorithms of social media platforms. In fact, by accommodating affluence and consumption as a given, all radical movements have struggled to make any meaningful change in the last few decades.

From modern slavery to climate change, too many campaigns focus on the ‘bad’ results of the global economy; ignorant of how the ‘positive’ effects of consumerism, and especially the screen-based digital world, warps people’s perceptions to protect and perpetuate itself.

E.g., take the simplistic phrase, often-repeated by Deep Ecologists and Neo-Luddites: “Turn it off”.

OK… turn it off and do what exactly? Let’s say I turn-off the power and gadgets in my life; now what? How does the average person work, travel, or buy and cook food?

“It has been, literally, the most blood thirsty, brutalizing system ever imposed on this planet. That is not civilization. That’s the great lie. That it represents civilization. Or if it does represent civilization, and that’s truly what civilization is, then the great lie is that civilization is good for us.”

The idea of ‘dropping out’ of today’s technologically-enabled society represents a ‘double-bind’; you can’t exclude yourself from society because the way it functions prevents you from doing so safely. Rather like a closed religious sect, turning off the technology in your life creates an automatic ‘social death’, that cuts you off from everything else in your life.

The opponents of environmentalists or anarchists use this argument as an attack: ‘turning-back progress is impossible’, and so continuing with ever-more technology is the only viable option for all humanity. The naïveté of the ‘turn it off’ statement, the assumption people can just drop the gadgets and walk away, embodies the reasons for its failure. On the positive side, though, by solving that failure, we might begin to make deep ecology, or anarcho-primitivism (see box, above), a practical option for the average person to seriously adopt.

Technology is not neutral. Technology reinforces the economic and political culture of the present-day, allowing the economic system to operate in the way it does:

Convenience food and ready-meals were not a conscious consumer choice – no one lobbied for them! They were designed to free people from food preparation, due to the excess of time most people (primarily women) were made to work outside the home – which made traditional food preparation from raw ingredients impossible.

Likewise, on-line banking isn’t a means to free people from a physical bank to manage their money (or realistically, their debt). It’s designed to allow finance corporations to cheaply manage people’s participation in the economic system – and in a way which gives them greater surveillance capabilities over people’s lives, to more easily algorithmically exploit them as a resource for profit.

“The people who are trying to make this world worse aren’t taking a day off. How can I?”

Bob Marley (after concert, two days after getting shot, December 1976).

The ‘gig economy’ is not simply the result of large employers conspiring to casualize employment practices. The more precarious nature of employment isn’t just the result of governments and corporations manipulating the laws and practices of employment. It’s the technologies behind ‘platforms’ and ‘human resource management’ – which trap people into an ever-more precarious jobs market managed by technology, not people.

Just as many people on the ‘political right’ dismiss poverty or unemployment as a “lifestyle choice”, so those on the left dismiss economic exploitation or polluting industries as a ‘choice’ of capital. The fact is all sides are trapped within this system because – by its nature – you can’t disengage the unwelcome side of the modern economy without disavowing its benefits too. Again, it’s a ‘double-bind’ for the business lobby too; anyone who doesn’t act like a ‘good’ businessman or capitalist will be put out of business by the ones who do.

You can’t leave the system, even though your prospects in it are dire. What you must do is replace it with something else; something that you can maintain yourself.

Yes, there are lots of reasons for why getting outdoors is good for you; but beyond all the health and mental well-being stuff, walking and camping creates a physical space in which you can learn the skills required for ‘downshifting’ – exiting this high-tech., high-cost, dead-end ‘modern’ lifestyle.

It sounds absurd, but having the ability to brew a bowl of rosehip tea on a hill, is a gateway towards a lifestyle revolution. It’s not the literal tea-brewing (see box, below); it’s the mind-set created by regularly and enjoyably undertaking such ‘uneconomic’ activities.

In a sense, walking and camping are the workable alternative to the simplistic ‘turn it off’ message: Learning to walk and camp, carefree and comfortably, relies on developing skills through practical experience; rather than a hard break, it creates a space to ‘decompress’ – to learn the skills to make a parallel lifestyle free from the restrictions of consumer society.

Let’s take tea… literally!

A perfect example of the domination of society by consumer actions, which in turn reinforce the economic interests which created them them, is Britain’s ‘favourite drink’: Tea.

Tea consumption isn’t just the result of colonial trade; it’s intrinsically tied to the urbanization of the British people alongside industrialization. Black tea was once an exclusive product, imported in small quantities from distant lands; it was symbolically a drink of the wealthy.

The Agricultural Revolution forced people from the land in step with the Industrial Revolution. That’s because as industrial urbanization created a market for bulk food commodities in towns, it allowed agricultural estates to modernize production with the machines produced by industry.

In the same way, the plant-based flavours people added to boiling water – which at its simplest is what tea is – would have traditionally been harvested for free in the landscape surrounding rural communities. As land clearance and inclosure took hold, the new populations in cities had to buy their tea, and that gave rise to a mass market for imported teas from the growing empire – which in turn reinforced the economic power of empire, promoting the evils it inflicted upon the world.

Today, this historic process has turned full circle: Most ‘ordinary’ people drink imported black tea; affluent consumers are more likely to drink herbal teas made from specially-produced herbs.

How to escape this situation?

The anarcho-primitivist solution: Do what our ancestors did and collect your own wild teas!

In order to preserve ancient common rights, paragraph 3 of section 4 of The Theft Act 1968 grants an exemption for the picking of wild plants. Foraging is not stealing, it is your ancient right! – which you must defend.

With access by a public road or right of way, you can pick what grows by the highway and make tea; or take it home to dry and keep (drying simply involves hanging bunches of stems from a hook so they air dry over a few weeks, after which they can be stored in air-tight containers).

Popular foraged teas, which are essentially leaves growing by the wayside, include: Dandelion leaves and/or flowers; stinging or dead nettles; members of the mint family (all edible) such as ground ivy; raspberry or blackberry leaf; yarrow leaves/flowers; rosehips (outer shell only, not the seeds); meadowsweet; or mugwort.

Even a small garden can produce herbs for tea with just a little effort, such as: sage; lemon balm; marjoram; mints; or just the edible weeds that grow there.

Black tea represents a single flavour. By collecting your own herbal tea you can experience a range of flavours, as well as the higher level of nutrition compared to highly processed black tea. More importantly, foraging for tea is a very easy skill to learn because most of the plants are easy to identify. That can then lead you on to developing your skills to identifying a wider range of food plants later.

Numerical Ramblings – ‘Why own-grown potatoes are better energy storage devices than lithium-ion batteries’

People obsess about electricity-producing technologies. Seldom do they think about the potential of something more hum-drum, like their food.

Environmentalists were traditionally opposed to cars. They also had an historic opposition to mining and the pollution caused by the production of electronics. Somehow though, with the advent of electric vehicles (EVs), most environmental groups have suddenly become pro-car and pro-electrics. They support electric cars as if they were an eco-gift from the gods.

There is a reason for this: Today, campaign groups are not campaigning to ‘save the planet’, but to ‘save our affluent lifestyle’. They might talk about climate change being the issue, but their dialogue is dominated by projects or policies that replicate affluent consumption pattens via other, (allegedly) more ‘sustainable’ means.

Electric cars are the perfect example of this disconnect. The green lobby support their use because they misunderstand how they are created, and why that is anti- not pro-environment.

In 2019, a special panel convened by the Natural History Museum wrote to the Climate Change Committee (CCC) as part of a consultation on the future policy on EVs in Britain. In their letter they expressed concerned about the availability of resources for the CCC’s proposals, questioning their viability:

“To replace all UK-based vehicles today with electric vehicles… represents just under two times the total annual world cobalt production, nearly the entire world production of neodymium, three quarters the world’s lithium production and at least half of the world’s copper production during 2018.”

The CCC ignored their querying of reality and went ahead with the policy of replacing all private cars with EVs – rather than other more resource efficient options like walking, cycling, and public transport. But let’s assume it was possible to get those resources.

The core of an EV is the battery and electric motor. Let’s just focus on the battery, since these days eco-forums seems obsessed with stories about “new, improved” batteries.

People obsess about electricity, and electricity producing technologies. Seldom, though, do they think about something hum-drum, like their food.

All batteries, from old-fashioned lead-acid to the latest lithium-ion (li-ion) cells, have a ‘storage density’: A measure of how much electrical energy they can store per unit of volume or weight. Often overlooked, it also takes energy to make the battery – a figure called ‘embodied energy’ – in addition to charging the battery.

In the same way, food has a certain amount of ‘energy storage’ as food calories. And to get those from potatoes we have to grow them, then cook them, using various energy sources.

Though it is said potatoes store more energy than lithium batteries, it’s more complicated than that. The figures must be expressed the same way. The big difference is the number of times you can do this: A li-ion battery can ideally be recharged 3,000 times; you can only eat a potato once.

For that reason it requires a figure for the ‘net energy’ of each cycle – how much energy is output on each cycle, less how much embodied and expended energy goes in to each cycle.

Reviewing various journal papers, the energy characteristics of a li-ion cell (rounding the figures up/down to the nearest 100) are shown in the table below. Yes, li-ion batteries consume lots of energy in production, but assuming they’re recharged 3,000 times each cycle only costs a fraction of that figure. Overall then, each cycle supplies -680kJ to -1,000kJ/kg.

| Comparison of potatoes and lithium-ion batteries for energy storage1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium-ion battery | Shop-bought potatoes | Own-grown potatoes | |

| Stored energy output, kJ/kg | 300 to 700 electric power |

3,300 food calories |

3,300 food calories |

| Embodied energy of ‘cell’ production, kJ/kg | 1,300,000 to 2,900,000 | 7,000 | 3302 |

| Cycle energy input, kJ/kg | 315 – 7353 grid power |

1,500 boiling |

1,500 boiling |

| Number of use cycles | 3,000 | 1 | 1 |

| Net energy per cycle, kJ4 | -681 to -1,001 | -5,164 | +1,470 |

1. Expressed in kilo-Joules (kJ) equivalent: 1 Watt-hour (Wh) is equivalent to 3.6kJ; 1 kilo-calorie (kCal) is equivalent to 4.2kJ. 2. Input:output calories of subsistence agriculture, 1:10, assumed from other studies. 3. Assumes 95% cell charging efficiency. 4. Energy storage – ((embodied en. ÷ no. cycles) + cycle energy) |

|||

“Hang on”, you say. “How can a battery supply a negative value of energy”. Well, it can’t. The system does.

Batteries only ‘store’ energy; meaning energy must be put into them first, as well as a fraction of the embodied energy invested. Overall electrical storage cells do not supply energy, they consume energy on each cycle.

The calculation for shop-bought potatoes is shown in much the same way. Take the calories supplied, and as we only eat them once just subtract the energy used in production plus the energy used in cooking. This gives a figure of -5,164kJ/kg.

“Hang on”, you say. “How can a potato supply less energy than it contains”. Well, it can’t. The system does.

Modern farming, producing bulk commodities for supermarkets, uses large amounts of fossil fuels and other inputs. E.g., 2% of the world’s energy supply goes into making fertilizer. Then there’s processing and transport on top, often spread across continents. A recent study found that perhaps 40% of global carbon emissions are tied up with agriculture – this is why!

The last column is ‘own-grown’. This assumes hand-digging and harvesting, saving and reusing seed, and not adding artificial nutrient inputs – but rather than use a ‘0’, it assumes the 1:10 calories in/out ratio for subsistence farming. These potatoes produce an actual surplus of +1,470kJ/kg.

While environmentalists obsess about EVs and battery technology, their ‘modern’ food supply quite possibly demands more energy, calorie per calorie, than cycling an EV battery, watt-hour per watt-hour. If they’d stop buying from supermarkets, and grew food locally using low-tech. methods, their diet might transform into supplying a truly ‘renewable’ energy surplus.

W.E.I.R.D.: THINKING BEYOND TECHNOLOGY – No.4, Midsummer 2021

A Free Range Activism Network Publication. Download other editions of ‘WEIRD’ at http://www.fraw.org.uk/frn/weird/index.shtml. Email any comments or feedback to weird☮frăwꞏörĝꞏuk. Issued under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA-4 license; you may freely distribute.