‘WEIRD’, A Free Range Journal – Issue No.2, Lammas 2020:

Welcome the Extinction

Welcome to this second edition where we directly ‘welcome the extinction’ of what passes for normality, in the hope that people will move on and organize for something better.

Download this edition

1A4 PDF – for printing at A4 single- or double-sided; or

2A3 PDF – for printing landscape A3 double-sided to create a folded/stapled brochure.

‘WEIRD’ is designed to print at A4, but will reduce to A5 and be about the same size as small newsprint. The A3 PDF will scale for double-sided A4 landscape

Issue No.2 Contents:

- Introduction – ‘Welcome the Extinction’

- For some this edition of ‘WEIRD’ will be a difficult, perhaps impossible reading exercize. Some will see it as an attack on cherished ideas. Others may reject it as a cynical dismissal of ‘environmentalism’.

- History File – ‘Tactics’

- An extract from ‘Rules for Radicals’ by Saul Alinsky, a log of civil rights organizing in 1950s and 1960s America.

- ‘Truth’ and the rise of ‘green technocracy’

- When laying claim to “reality”, we must be careful we are not deceiving ourselves.

- “Eat the Rich” – Like it or not, the environment is a ‘class’ issue

- The contradiction at the heart of the environment movement preventing action to create ‘true’ ecological change.

- Climate change is not the problem; everything is

- There are between ten and twenty ecological trends, any one of which could collapse the ‘modern’, technologically-enabled human system. Why then focus most of our energies on just one?

- The Ecocide Long List

- A list of ecological trends which may create serious disruption to modern-day ‘technological’ society.

- ‘Beyond Politics’ – Rebels without applause

- When metropolitan leftist politics disappears up its own press release.

- Environmentalism’s silence over ‘the limits to growth’ is an offence akin to climate denial

- Why does the environmental movement complain about ‘climate change denial’, when they ignore the scientific research on the limits to economic growth?

- “Nine meals from anarchy?” That’s not our kind of anarchy!

- It’s time for activists to reclaim the deep ecological roots that inspired the environment movement, and create the resources and energy that supports humans, not machines.

- The trouble with ‘consumer vegans’

- Meat-free consumerism has no soul, nor any point.

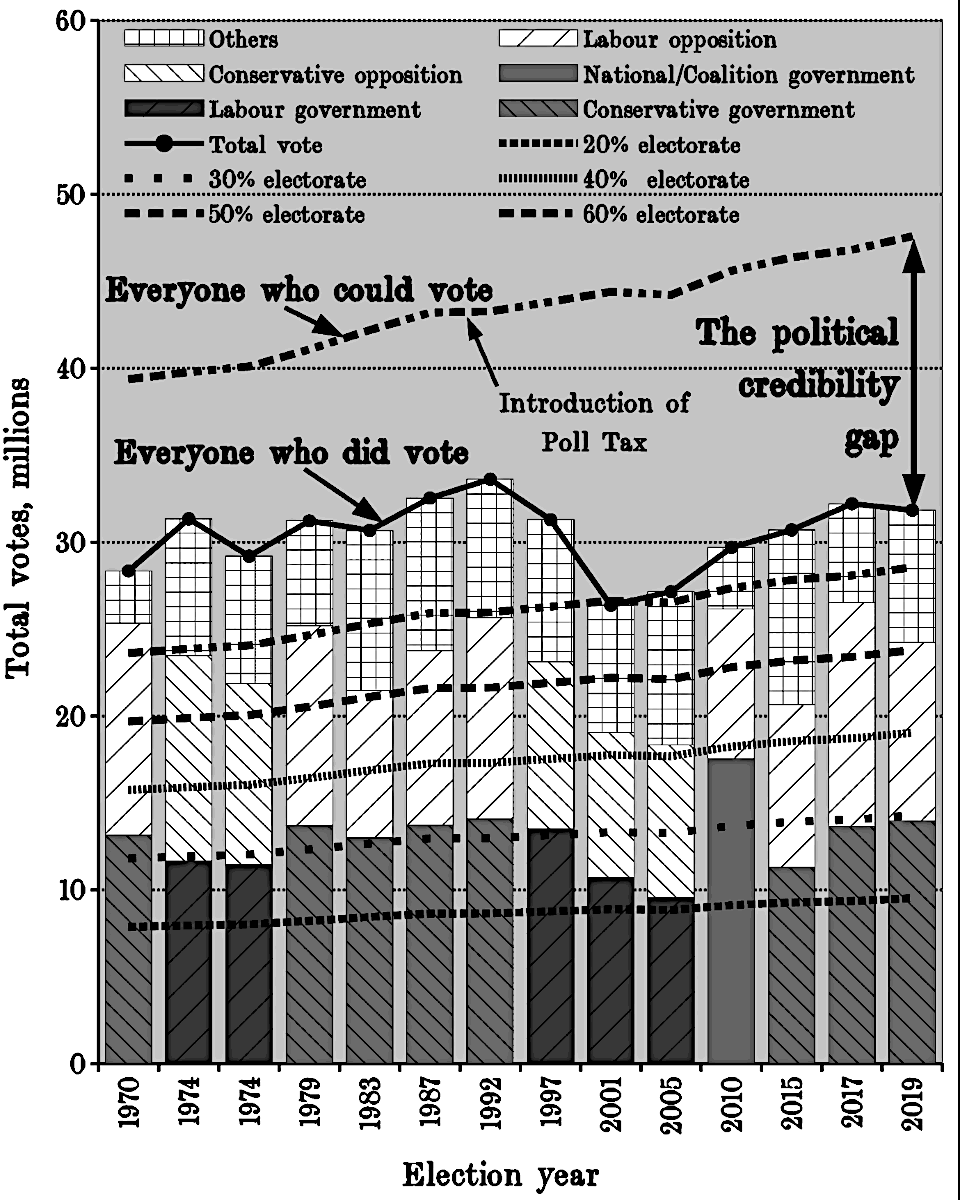

- Numerical Ramblings – ‘Well I didn’t vote for him’

- Why Britain’s electoral system is incapable of delivering a radical alternative to ‘business as usual’.

Introduction – ‘Welcome the Extinction’

For some this edition of ‘WEIRD’ will be a difficult, perhaps impossible reading exercize. Some will see it as an attack on cherished ideas. Others may reject it as a cynical dismissal of ‘environmentalism’.

No matter. What we seek to offer in this edition is our ‘experience’; an evaluation of the ecological debate today, and why it has become a mythical ‘hyper-reality’ that no longer represents, and so cannot possibly hope to tackle, the problems we presently face.

‘WEIRD’ is the newsletter of the Free Range Network (FRN).

The FRN started 25 years ago not as an organization, but as a network of like-minded activists – and that is pretty much how it has stayed. We are so set on not developing an ‘organization’ that we evolved a term for how we work: ‘dysorganization’ (‘dys-’ being a prefix that says a formal ‘organization’ would be bad for our way of working).

We’ve never had a budget. We’ve never had a plan. We swap data. We share skills and knowledge. We occasionally muck-in to help each other’s real-world events or actions. And for those at the core of the group, official condemnation, arrest, or court injunctions – or in the worst case being ‘unfriended’ on social media – are not the exception, they are a badge of critical success.

FRN became that because, in the late 1990s, the network attracted “refugees” from other environmental organizations.

Many of these people, in the rush of mainstream eco-groups to adopt the new mantras of ‘green consumerism’, had been marginalized or even ejected because they were considered ‘too radical’. Within the FRN though, such singular commitment to change was welcome.

Since early 2019 we’ve noticed a new trend. We’re picking up new ‘refugees’ from Extinction Rebellion (XR).

Figures within FRN have always honestly discussed their distrust of the XR organization, and in particular their seemingly messianic need to get arrested in order to prevent ‘climate breakdown’. The few figures who inspire XR, in their zeal to pursue arrest as their primary tactic, have routinely ignored the views of people who have been doing that kind of thing for years.

Within the Free Range Network, where individuals have decades of experience in grassroots organizing, collectively representing centuries of experience of these issues, we know that the ‘truth’ (something which, again, XR seem to monopolize) is far, far more complicated.

At the Green Gathering in 2019 XR had a large stall area at the centre of the site – with, it seemed, no permanent presence to talk to those visiting it.

Directly opposite was the FRN’s stall.

“…in the Western world nowadays it seems less useful to ascribe alienation to persons or groups out of a missionary drive to cure others of something they are either blissfully unaware of, or perfectly content with. The individual living in a world saturated with communication media is offered the possibility of thoroughly identifying with different alternative life scenarios, and at least in much of the Western world many of these scenarios can be realized if one is willing to pay the inevitable price. But a lifetime is limited, and so are the scenarios one can choose and try to realize.”

Sociology of Alienation, F. Geyer, ‘Encyclopaedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences’ (2001)

As the public visited the XR stall and found no one home, then exited and saw our stall directly opposite, offering something similar, and so they made a bee-line for us – and we gladly received them.

Over the week we also had a lot of visits from XR-types too: Some very ‘formal’, stressing the organizational matras (where we stressed them out); and many more ‘informal’, from those wanting a different perspective on activism (where we relieved their stress).

This edition of ‘WEIRD’ is a distillation of our experiences handling those general enquiries from the public, and the complaints of an increasing number of XR dissenters who feel that (in oft-said words) “there’s something wrong”.

‘Extinction’ is a complex issue. One which few choose to logically consider when blindly using the term as a justification for action. In this issue we hope to rectify that by looking are what it really means.

History File – ‘Tactics’

An extract from ‘Rules for Radicals’ by Saul Alinsky, a log of civil rights organizing in 1950s and 1960s America.

Written by Saul D. Alinsky in 1971, ‘Rules for Radicals’ is a work which logged the experiences of civil rights organizing in 1950s and 1960s America. This extract is from the chapter entitled, ‘Tactics’. We include this because so often when we talk with XR people we mention Saul Alinsky and get the response, “who?”; or mention his book and get the response, “what?” We can think of no higher recommendation to include his work here.

“TACTICS MEANS doing what you can with what you have. Tactics are those consciously deliberate acts by which human beings live with each other and deal with the world around them. In the world of give and take, tactics is the art of how to take and how to give. Here our concern is with the tactic of taking; how the Have-Nots can take power away from the Haves.

For an elementary illustration of tactics, take parts of your face as the point of reference; your eyes, your ears, and your nose. First the eyes; if you have organized a vast, mass-based people’s organization, you can parade it visibly before the enemy and openly show your power. Second the ears; if your organization is small in numbers, then do what Gideon did: conceal the members in the dark but raised in and clamor that will make the listener believe that your organization numbers many more than it does. Third, the nose; if your organization is too tiny even for noise, stink up the place.

Always remember the first rule of power tactics: Tactics Power is not only what you have but what the enemy thinks you have…

Power has always derived from two main sources, money and people. Lacking money, the Have-Nots must build power from their own flesh and blood. A mass movement expresses itself with mass tactics. Against the finesse and sophistication of the status quo, the Have-Nots have always had to club their way. In early Renaissance Italy the playing cards showed swords for the nobility (the word spade is a corruption of the Italian word for sword), chalices (which became hearts) for the clergy, diamonds for the merchants, and clubs as the symbol of the peasants.

The second rule is: Never go outside the experience of your people. When an action or tactic is outside the of the people, the result is confusion, fear, and retreat. It also means a collapse of communication, as we have noted.

The third rule is: Wherever possible go outside of the experience of the enemy. Here you want to cause confusion, fear, and retreat.

General William T. Sherman, whose name still causes a frenzied reaction throughout the South, provided a classic example of going outside the enemy’s experience. Until Sherman, military tactics and strategies were based on standard patterns. All armies had fronts, rears, flanks, lines of communication, and lines of supply. Military campaigns were aimed at such standard objectives as rolling up the flanks of the enemy army or cutting the lines of supply or lines of communication, or moving around to attack from the rear. When Sherman cut loose on his famous March to the Sea, he had no front or rear lines of supplies or any other lines. He was on the loose and living on the land. The South, confronted with this new form of military invasion, reacted with confusion, panic, terror, and collapse. Sherman swept on to inevitable victory. It was the same tactic that, years later in the early days of World War II, the Nazi Panzer tank divisions emulated in their far-flung sweeps into enemy territory as did our own General Patton with the American Third Armored Division.

The fourth rule is: Make the enemy live up to their own book of rules. You can kill them with this, for they can no more obey their own rules than the Christian church can live up to Christianity.

The fourth rule carries within it the fifth rule: Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon. It is almost impossible to counter-attack ridicule. Also it infuriates the opposition, who then react to your advantage.

The sixth rule is: A good tactic is one that your people enjoy. If your people are not having a ball doing it, there is something very wrong with the tactic.

The seventh rule: A tactic that drags on too long becomes a drag. Man can sustain militant interest in any issue for only a limited time, after which it becomes a ritualistic commitment, like going to church on Sunday mornings. New issues and crises are always developing, and ones reaction becomes, “Well, my heart bleeds for those people and I’m all for the boycott, but after all there are other important things in life” — and there it goes.

The eighth rule: Keep the pressure on, with different tactics and actions, and utilize all events of the period for your purpose.

The ninth rule: The threat is usually more terrifying than the thing itself.

The tenth rule: The major premise for tactics is operations that will maintain a constant pressure upon the opposition. It is this unceasing pressure development that results in the reactions from the opposition that are essential for the success of the campaign. It should be remembered not only that the action is in the reaction but that action is itself the consequence of reaction and of reaction to the reaction, ad infinitum. The pressure produces the reaction, and constant pressure sustains action.

The eleventh rule is: If you push a negative hard and deep enough it will break through into its counter-side; this is based on the principle that every positive has its negative. We have already seen the conversion of the negative into the positive, in Mahatma Gandhi’s development of the tactic of passive resistance.

One corporation we organized against responded to the continuous application of pressure by burglarizing my home, and then using the keys taken in the burglary to burglarize the offices of the Industrial Areas Foundation where I work. The panic in this corporation was clear from the nature of the burglaries, for nothing was taken in either burglary to make it seem that the thieves were interested in ordinary loot — they took only the records that applied to the corporation. Even the most amateurish burglar would have had more sense than to do what the private detective agency hired by that corporation did. The police departments in California and Chicago agreed that “the corporation might just as well have left its fingerprints all over the place.”…

The twelfth rule: The price of a successful attack is a constructive alternative. You cannot risk being trapped by the enemy in his sudden agreement with your demand and saying “You’re right — we don’t know what to do about this issue. Now you tell us."

“These rules make the difference between being a realistic radical and being a rhetorical one who uses the tired old words and slogans”

Saul Alinsky, (Preface) ‘Rules for Radicals’ (1971)

The thirteenth rule: Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.

In conflict tactics there are certain rules that the organizer should always regard as universalities. One is that the opposition must be singled out as the target and “frozen.” By this I mean that in a complex, interrelated, urban society, it becomes increasingly difficult to single out who is to blame for any particular evil. There is a constant, and somewhat legitimate, passing of the buck…

One big problem is a constant shifting of responsibility from one jurisdiction to another — individuals and bureaus one after another disclaim responsibility for particular conditions, attributing the authority for any change to some other force. In a corporation one gets the situation where the president of the corporation says that he does not have the responsibility, it is up to the board of trustees or the board of directors, the board of directors can shift it over to the stockholders, etc., etc…

It should be borne in mind that the target is always trying to shift responsibility to get out of being the target. There is a constant squirming and moving and strategy-purposeful, and malicious at times, other times just for straight self-survival — on the part of the designated target. The forces for change must keep this in mind and pin that target down securely. If an organization permits responsibility to be diffused and distributed in a number of areas, attack becomes impossible…

The other important point in the choosing of a target is that it must be a personification, not something general and abstract such as a community’s segregated practices or a major corporation or City Hall. It is not possible to develop the necessary hostility against, say, City Hall, which after all is a concrete, physical, inanimate structure, or against a corporation, which has no soul or identity, or a public school administration, which again is an inanimate system…

I hesitate to spell out specific applications of these tactics. I remember an unfortunate experience with my {book} ‘Reveille for Radicals’, in which I collected accounts of particular actions and tactics employed in organizing a number of communities. For some time after the book was published I got reports that would-be organizers were using this book as a manual, and whenever they were confronted with a puzzling situation they would retreat into some vestibule or alley and thumb through to find the answer.

There can be no prescriptions for particular situations because the same situation rarely recurs, any more than history repeats itself. People, pressures, and patterns of power are variables, and a particular combination exists only in a particular time — even then the variables are constantly in a state of flux. Tactics must be understood as specific applications of the rules and principles that I have listed above. It is the principles that the organizer must carry with him in battle. To these he applies his imagination, and he relates them tactically to specific situations.

For example, I have emphasized and re-emphasized that tactics means you do what you can with what you’ve got, and that power in the main has always gravitated towards those who have money and those whom people follow. The resources of the Have-Nots are (1) no money and (2) lots of people. All right, let’s start from there. People can show their power by voting. What else? Well, they have physical bodies. How can they use them? Now a melange of ideas begins to appear. Use the power of the law by making the establishment obey its own rules. Go outside the experience of the enemy, stay inside the experience of your people. Emphasize tactics that your people will enjoy. The threat is usually more terrifying than the tactic itself. Once all these rules and principles are festering in your imagination they grow into a synthesis.

Lastly, we have the universal rule that while one goes outside the experience of the enemy in order to induce confusion and fear, one must not do the same with one’s own people, because you do not want them to be confused and fearful…

I must emphasize that tactics like this are not just cute; any organizer knows, as a particular tactic grows out of the rules and principles of revolution, that he must always analyze the merit of the tactic and determine its strengths and weaknesses in terms of these same rules.”

‘Truth’ and the rise of ‘green technocracy’

When laying claim to “reality”, we must be careful we are not deceiving ourselves.

“What is truth?”

Don’t expect an answer to that. People have been messing around with that hot potato for the past few millennia of recorded history.

What we’re trying to get at is, when you have an everyday conversation how do you tell ‘the truth’?

Now, this might be hard for you to admit to yourself, but for most people they’re not telling the truth that they ‘know’ to be true; they’re repeating a statement they have been told is true. Though certain groups might demand that people “tell the truth”, the reality is that most people choose to hear the truth that reflects their view of the world… Therein lies the problem!

Who do you trust? Why is it you trust them and not another source?

To hold conversations as simply as possible, how do you reference information you ‘know’ to be true without endlessly debating details and definitions?

Truth is, you don’t!

Truth is, most people defer to a person or agency who holds ‘authority’.

Who then is the authority for the environment movement?

George Monbiot? Some of his statements, e.g. on energy or rewilding, have been very suspect of late.

In the modern world ‘truth’ is related to ‘rationality’. The idea that rather than one person’s opinion, there is a set of facts that can be proven against collectively known measurements or observations.

Demonstrably that’s not true!

If we look at how factual truth is managed in complex societies it is not the deliberations over data verified by ‘ordinary’ people that sets the rule. Due to the complexity of the modern world, what is or is not ‘true’ is always a value set by one or more people who – through positions in academia, the media, business, or politics – claims something to be true or not.

In complex societies then, what is ‘true’ is inevitably a matter of ‘authority’, not ‘facts’.

Why does ‘fake news’ or ‘political spin’ work? Because the world is too complicated, and too pressured, to check everything you’re told – especially when it agrees with your own (ill-informed?) view of the world.

As the green movement has shifted towards marketing technology rather than creating change, the debate has ceased to be one where ordinary people decide ‘what is true’. Instead they have to defer to the ‘green technocracy’ – the network of pundits, groups, lobbies, or academics – who have the time to do research and find ‘the truth’.

Taking-away decisions over what is ‘true’ about technology and change also means taking-away their freedom to chose the form or function of that technology – and what it is there to do for them. Hence, if you deny people a role in decision-making, all arguments for change become dictatorial instead of a free choice over what is ‘true’.

There is no one source of authority for eco-issues. There are many parallel ones, operating simultaneously, for business, governments, and factions within the movement. Those making claims don’t really care; it’s ‘their’ truth they’re saying, and that’s all that is important.

The difficulty is that the public haven’t got a clue who is telling the truth because so often these truths are contradictory – confusing the substance of message being given.

Irrespective of who says it, right now things are said about climate change or eco-destruction that are assumed, but very rarely tested and proven to be true. That’s because by deferring to ‘science’ or ‘green technology’ to “save the planet”, campaigners exclude the public, and quite often themselves, from holding a detailed understand of what that solution does – “it’s too difficult!”

To make progress the movement faces its greatest challenge: To be honest to itself about the ‘truth’. For if it can’t accept the truth itself, how can tell anyone else?

For example, as outlined elsewhere in the newsletter:

Evidence indicates the struggle to save the environment from irreparable damage has now been lost (see ‘Climate change is not the problem; everything is’) – and so the priority now is adaptation to future change;

The demographics of the movement mean those actively supporting it are the very group causing the greatest damage (see ‘Eat the Rich – Like it or not, the environment is a class issue’) – hence and why for them technological change will always be preferable in order to preserve their own affluent lifestyles.

In any case, the evidence shows we’re now at the ‘Limits to Growth’, and so a contraction of lifestyle is inevitable (see ‘Environmentalism’s silence over the limits to growth is an offence akin to climate denial’) – and the priority is to control that contraction so it is fair for all not a free for all.

Therein lies the truth to the ‘green technocracy’ conundrum (the subject at the heart of this article); and the solution to creating ‘progress’ rather than just ‘change’.

“Eat the Rich” – Like it or not, the environment is a ‘class’ issue

The contradiction at the heart of the environment movement preventing action to create ‘true’ ecological change.

The comedian Frankie Boyle says that he is making a commitment to go carbon neutral by changing his diet, not to veganism but to cannibalism. What he fails to realize is that if he ate someone richer than himself he could arguably go one better and be carbon negative.

In an ecological context then, never has that old worn phrase “eat the rich” been so true (ignore the group Class War, that phrase was first popularized by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the Eighteenth Century!).

Forget politics with a big ‘P’ here; of the centre, the left, or the right. The fact is that the people who make up the majority of the membership of the environment movement (and politics generally) – the middle class – are the problem. Their lifestyles are emblematic of the modern economic dogma that is consuming the Earth – affluence.

The people who run the environmental movement – certainly in Britain – are not simply middle class; there’s a smattering of public school, political elites, and minor gentry in there too. Their innate (small-’C’) conservatism aside, that also has thean unfortunate consequence: The mainstream’s solutions to ecological destruction, based upon options that preserve their own relative economic advantage. That, inevitably excludes the most fast acting and proven means of ‘saving the planet’: Consuming less.

Many in the environmental movement celebrate the second Earth Summit at Rio in 1992 (yes, it was the second; the first in Stockholm in 1972 is often forgotten, as is the 2002 third one in Johannesburg in 2002). It was there that the first global treaty on climate change was signed.

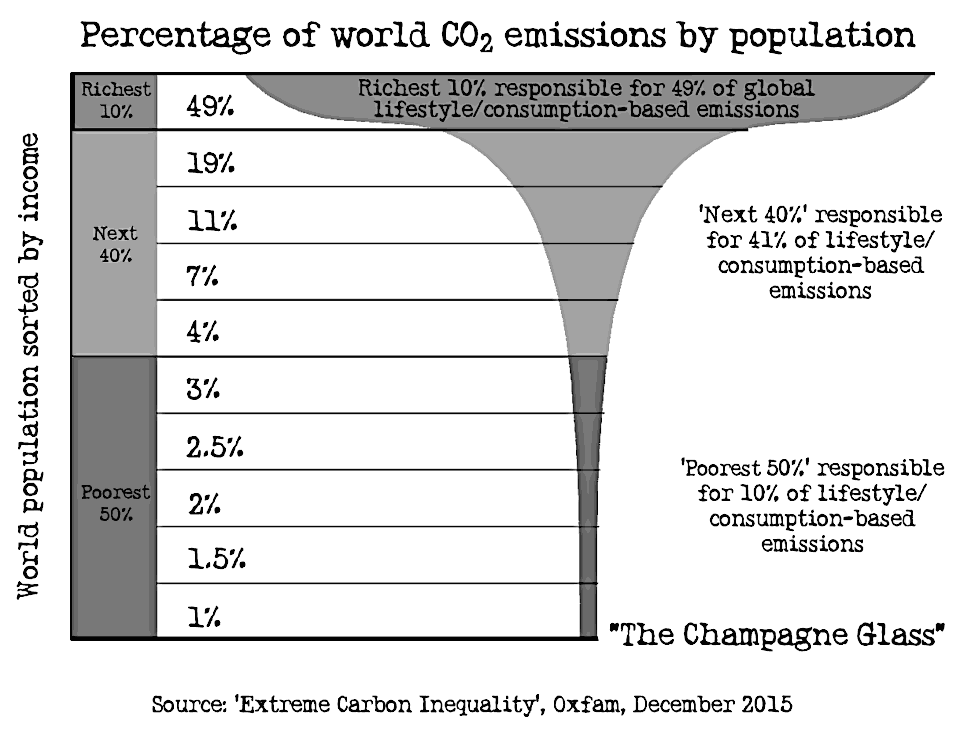

Also in that year the third UN ‘Human Development Report’ was published. Inside was a graph, since called ‘the champagne glass’, which showed the levels of global resource consumption allocated by income.

It was ignored; particularly at the Rio Earth summit – and remained that way for over twenty years.

In 2015 Oxfam updated it in their ‘Extreme Carbon Inequality’ report – using the latest data on ‘embedded carbon’ and ‘supply-chain’ emissions.

What ‘the champagne glass’ shows is not national emissions, which is what dominates the debate today; but personal emissions sorted by global levels of income. Not surprizingly consumption by individuals, and the impacts of that consumption, are primarily the result of affluence; with the top 10% to 15% of the world’s population emitting well-over half the world’s carbon emissions.

The bottom half? They emit 10%.

Ask yourself, where do you see this figure routinely discussed in climate change campaigns? If only 10% of the world’s population represent half the emissions, shouldn’t we target their emissions first, as a priority?

The fact is, mainstream climate change activism routinely ignores economic inequality as part of their work – perhaps because the social profile of most of those involved in these campaigns, nationally and globally, falls within that top 10% who emit the most.

If the richest are responsible for the most of the emissions, why don’t they simply cease being affluent? But as poet John Cooper-Clark said, “there’s one thing that money can’t buy: Poverty”.

The middle class response to ecological destruction has always been based on managerial, and/or technological change, because thatss what they know and understand.

The core of present-day ‘aspirational’ economics is centred on consumption. Thus green technology is a compromize to preserve that lifestyle and set of values without painful lifestyle changes.

The issue of the environment, lifestyles, and consumption, had been the dominant issue of the 1970s ecology movement. Then in the 1980s certain figures in Britain – in particular Jonathon Porritt and Sara Parkin – decided to steer the movement in a different direction.

That process began with tokenistic, but psychologically significant changes – such as renaming ‘The Ecology Party’ as ‘The Green Party’. Then they shifted the emphasis from a discussion about the impacts of human consumption, and the ‘Limits to Growth’, to one of managing consumption through a focus on ‘green consumerism’ and ‘green technology’.

Saving the planet no longer needed to be painful. You just had to make the right decisions over what to buy!

Problem was, under this model the only people who could practically ‘go green’ were those with the wealth to consume the ‘right kind’ of products – which were sold at a premium as they were aimed at a more affluent audience.

It also ignored reality that you only had rights, or the ability to act as a ‘green consumer’, within the capitalist frame of economics. The idea that other systems or economic options might be feasible was no longer up for debate.

So, ‘game over’ for more radical ideas!

Where did the ‘the poor’ fit into this vision for change? Fact was, they didn’t – other than as a group to be dictated to.

Needless to say this ‘pragmatic’ course of action not only won acclaim from government and industry groups, as time passed it also won grants and sponsorship from the very industry groups causing the problems. As a result the ordinary membership (which had started to fall in the early 1990s) were increasingly marginal to decision-making. With funding and sponsorship up for grabs, decision-making by the management teams of green lobby groups – which is what these former ‘action’ groups now were – became ever-more business- and technology-friendly.

At the time they took these decisions, Porritt and Parkin had no proof that this course of action was any better for the planet than the agenda advocated by the movement in the 1960s and 1970s. What it represented was a set of more palatable policies for the aspirational middle class, and so thus the hope of more, and more affluent members.

“CD thought back to the lads he had been at school with. He felt fairly confident that it would take something more convincing than the offer of a massage from Karen to turn them onto an alternative culture. The appropriation of radical thinking by lazy, self-obsessed hippies is a public relations disaster that could cost the earth.”

Ben Elton, ‘Stark’ (1989)

Thirty years on, the evidence suggests that they were completely wrong, if only because the mass membership and the budgets that offered never materialized.

In the interim the cost of London-centric office space and salaries sky-rocketed, consuming much of that new income. Porritt and Parkin’s ‘professionalization’ of the movement meant staff in these groups can now hope to move-on to government quangos or ‘third sector’ charities – rather than “saving the planet” and removing the need to have the organization in the first place.

For the claims of affluent green consumerism to be valid it is necessary to ‘decouple’ economic growth from its impacts on the environment. Over the last 20 years more and more research has demonstrated this to be impossible – and yet mainstream groups still cling to technological visions for change based upon the notion of decoupling.

The Free Range Network have been holding events around these issues since 1999; and people within the network have been tracking and publicizing the new research on this issue too. Over that time the overwhelming response from mainstream eco-groups has not been criticism or arguments against this evidence. Their main response has been silence.

They’ve refused to engage with this research, instead diving ever deeper into grandiose claims about the benefits of green technologies, ‘doughnut’ or ‘circular’ economics, and Green New Deals.

Of late though the level of academic interest in this issue has grown to a point level where it has started to break-out of the more fringe academic journals – on ecological economics or industrial ecology – into more mainstream science journals:

Research commissioned by the UK government’s own environment department in 2008 showed that, when you add in the impacts of our imported manufactured goods, our carbon emissions have not decreased at all – in fact they are now three times higher than the government reports to the UN each year.

One recent paper in the journal Nature Communications showed that growth in affluence has increased resource use and pollution faster that it can be reduced through new technology – meaning only a real-terms contraction in consumption can actually reduce impacts overall.

A study in PNAS showed on average wealthy households have ecological footprints 25% higher than lower-income households – and in affluent suburbs these can be 15 times higher than nearby poor neighbourhoods.

A study published in 2016 in the journal Environmental Conservation showed that while green consumer choices were a good predictor of support for environmental causes, they did not demonstrate a lower impact upon the environment as a result – due to their generally higher levels of consumption overall.

What the research shows is that relatively it is the poor who are ‘greener’, and it is affluent green consumers who are consuming the planet. No level of ‘green consumerism’ can ameliorate the global impacts of the most affluent 10%-20% of the population, certainly not in any way that reduces global inequality.

What we’re seeing today is that the depletion of finite resources, which was a rallying point for environmentalism in the 1970s, is now beginning to bite – making the movement’s advocacy of technological solutions ever-more tenuous.

Again, that’s also not good news for the global poor. Most of the finite resources critical for green and digital technologies are consumed by the world’s wealthiest citizens, meaning there will be little to secure their future options.

Leaders within the environment movement, if they are to make progress, must drop the pretence. It’s time to admit the past policy mistakes. They have to recognize that affluence is the problem, not an enabler of solutions to our problems. They must renounce the panacea of technologically-enabled change and focus on what is essential: Consumption; and the global limits to lifestyle.

Climate change is not the problem; everything is

The environment movement has become ‘monotheistic’ in its belief in climate change above all other ecological evils. Depending upon the boundaries you set, there are between ten and twenty ecological trends, any one of which could collapse the human system. Why then focus most of our energies on just one?

In the early 1990s, when the risk was finally taken seriously, Britain was one of the countries expected to weather a global flu pandemic really well. It’s relative economic strength, large medical/pharmaceutical sector, and centralized government and health services, gave Britain a strategic advantage over many other states.

Hindsight is a great leveller. And little New Zealand… who knew?

Covid-19 is a test case for how Western hubris over their technical and managerial expertize can so easily unravel, leaving ordinary (a.k.a poor/average) people bearing the cost of that failure.

There are many other ecological trends that, individually, have the potential to disrupt ‘modern society’ to an even worse level than corona virus has. The problem is that as each trend grows, and because they are all interconnected, it becomes progressively harder to solve any one of them.

Remember, a ‘crisis’ is just a relatively simple ‘problem’ that’s been ignored for too long.

Flu is not the problem; nor climate change either. The problem is that modern society has become so complex it is difficult to understand how different risks might interact to disrupt systems; and in turn, it is difficult to assess the risks of what might happen when things do go wrong ‒ the best recent example being the financial crash of 2008.

The problem is not one ‘thing’, it’s that there are a large number of inter-related ‘things’ that all pose the same risk (see next section) ‒ up-ending the complex web of physical and economic relationships that make the ‘modern’ way of life function seamlessly.

All the major eco-campaign groups should be aware of this. At a minimal level they do acknowledge the fringe of these issues. But the reality is (as set out in the section before) the mainstream environmental movement cannot handle the ‘truth’ about ecological collapse. They must always be fluffy and positive about technology; for once you accept ‘technology cannot save you’ that negates the value of your presentday and future lifestyle choices.

Is climate change a catastrophic risk to humanity?

Absolutely it is.

In which case does climate change pose an extinction level outcome for humanity?

No!

Climate change is the end of modern humans, but it’s unlikely to be the end of humanity.

Humans are just too damn clever, and we have survived equally disruptive climatic changes over the past 100,000 years without the benefits of modern scientific knowledge. That’s because ancient humans had something more valuable than technology; they had an innate awareness of their immediate ecology, and their role in living interdependently within it.

The reality is that there are some low-tech, often indigenous communities in Northern Canada, Southern Argentina, or Eastern Siberia, for whom future survival will be entirely possible. They understand the fundamental importance of having a direct association with the land and the support it gives ‒ in terms of food and resources ‒ and so will probably keep on keeping on (unless states ‘go nuclear’ in the coming conflicts over resources).

Of course, that isn’t a description ‘you’, is it?

The modern eco-movement has lost its awareness of ‘deep ecology’, and why it is critical to solving today’s ecological problems. What campaigners mean when they say ‘extinction’ is the end of their own affluent way of life. Though they dress it up in some form of fluffy altruism for the planet, that masks the reality of what they advocate; that there are steps to solving the global ecological crisis they will not consider… such as ending the relative ‘affluence’ of the top 15%.

OK then, what are the obstacles?

One example: Research shows pollution is growing as economic growth increases demand faster than new technology reduces it.

A good example would be cars. Forget the 4x4s used on urban roads. Even for regular cars, all that air conditioning, motorized heated seats, and in-car entertainment, adds to bodyweight and power consumption. That is why, comparing ‘like with like', the life-cycle efficiency of motor vehicles in the past 40 years has worsened even though the engine at its core is more efficient.

The best alternative to the car is… No car. It’s removing the need for mechanized transport.

The response to that is usually, “but how will I get to the office in the city?”. Well, you won't!

The everyday factors driving the ecological decisions of the 10% to 15% of the world’s most affluent citizens just don't apply to the needs of the other 80-odd percent. It’s about time they realized that.

The reason 10% of the world’s population use most of the resources, and cause most of the pollution, is that their lifestyle self-justifies those choices; consumption is socially constructed to increase with a higher salary.

That’s the deeper reality here (explored in the next two articles). To riff on Clinton’s maxim, “it’s your lifestyle, stupid!” We could write an entire newsletter on each ‘cause’ listed in the ‘ecocide’ box, but the answer would ultimately be the same. So why not just be honest with ourselves and say that?

The Ecocide Long List

This is a list of ecological trends which may create serious disruption to modern-day ‘technological’ society. It is in no specific order in terms of ‘how bad’ each is; they’re all ‘bad’ for those who enjoy the affluent ‘Western’ lifestyle. Note it excludes purely natural events such as super-volcano eruptions, coronal mass ejections, or asteroid strikes.

- Affluence & urbanization

- The trend that drives everything – continued high levels of consumption are not possible on a finite planet. Affluence is a state of mind, not a physical necessity for a comfortable life – in the end the impacts of that lifestyle for the many outweigh the benefits for the few who enjoy it (see rest of list!)

- Antibiotic resistance

- Though rather ignored in the pandemic, primarily driven by intensive agricultural practices, antibiotic resistance poses a fundamental threat to to the healthcare system we have enjoyed for the last seventy years.

- Biodiversity loss

- It’s not simply it’s ‘bad’ to lose a species of fully animal. Biodiversity loss disrupts the local and global ecological moderation of food webs, water-cycles, nutrient-cycles, and thus ultimately the global climate.

- Carbon cycle disruption

- A.K.A “climate change”. Carbon emissions are as much an issue of carbon cycling as they is about the weather. E.g. we’re stripping carbon from the soils as a result of intensive farming, which is having major impacts on soils, wildlife, and river systems.

- Dependency on digital networks

- The more lifestyles are mediated by technology, the failure of the digital networks underpinning those systems poses an ever-greater threat to the well-being those dependent on them – and the operations of industrial mechanisms connected to it.

- Economic collapse

- In the modern world money doesn’t exist (it’s not secured against physical assets, so it’s value can suddenly fall). Problem is, the world’s political leaders believe it does, and so a collapse of the economic system can have a knock-on for most of the increasingly urbanized populations on the planet.

- Energy resource depletion

- This isn’t just a matter of fossil fuels – all of which are now experiencing supply issues that could disrupt the global economy. The metals used in wind turbines or PV are equally finite, and represent a limit to how much energy the world is able to produce.

- Geoengineering

- Fossil-fuelled climate change itself is an experiment in ‘geo-engineering’. Think how much mess we can make if we try and do it for real! Unfortunately the world’s affluent states increasingly see this as their only option to guarantee their future lifestyles.

- Global human/plant pandemics

- Covid-19 speaks for itself. Thing is, right now there are also global food plant pandemics that pose an equal threat to food supply – and which will only get worse due to biodiversity loss and climatic change.

- Groundwater depletion

- Hundreds of millions of people are directly (drinking water) and indirectly (food crop irrigation) dependent upon ‘fossil water’. In some of the world’s major food growing areas that water supply is now running out, and may be gone in 10-20 years.

- Kessler syndrome

- Ever seen the film, ‘Gravity’? As we put more junk in space, the more likely it is that a ‘chain reaction’ of impacts could knock-out all the satellites in low orbit – leading to major consequences for everything from global ‘just in time’ deliveries to electricity supply failures.

- Metal minerals depletion

- We are still in the ‘Stone Age’. E.g., mobile phones use two-thirds of all the elements known to science, mostly produced from finite mineral resources – and many of these ‘critical metals’ are running short.

- Nitrogen cycle disruption

- As we pull nitrogen from the air and spread it on farmland it disrupts the natural ecology every bit as much as climate change – and there’s so much ‘N’ already ‘in the system’ that even if we stopped tomorrow, it will continue to disrupt our rivers and oceans for a couple of centuries.

- Nuclear war

- Recent research shows that even a small-scale nuclear conflict – e.g. India-Pakistan or Israel-Iran – could have global consequences in terms of a ‘Nuclear Winter’.

- Ozone depletion

- CFCs, the chemicals in sprays and fridges, have still not gone away. Unfortunately research also raises the possibility that the ‘hydrogen economy’ – the much talked-of boost to using renewable energy globally – could also cause damage to the Ozone Layer from large-scale hydrogen leakage.

- Persistent pollutants

- Plastic is a ‘persistent’ pollutant – and people are excited about it because they can see it. Thing is there’s also a few hundred ‘invisible’ persistent chemicals building up in the environment – from pesticides and flame retardants to the Teflon in your saucepans – that pose a threat to human and natural life for decades to come.

- Phosphate rock depletion

- Intensive agriculture only exists because of the mining of phosphate rocks. We may only have another 40-50 years of that, while we add another billion or two population. Then what? All the alternatives for phosphorous production use more energy and resources per unit of ‘P’ delivered.

- Phosphorous cycle disruption

- Like nitrogen, as we add more phosphorous to the world’s land, rivers, and oceans it has deleterious effects on natural life, in particular fuelling the aquatic ‘dead zones’ in oceans off of major continental river basins.

- Political/economic inequality & debt

- Affluence is a Ponzi scheme; and debt an ‘IOU’ for future pollution and consumption. It must fail as there are not enough resources on the planet for everyone to have that way of life and pay those debts. Be it climate change or peak oil as the cause, the whole system must collapse eventually.

- Soil erosion

- Growing crops in soil is the most resource-efficient means of production because nature’s ‘ecosystem services’ do most of the work. It takes nature a century to make an inch of soil. Around the world we’re losing soil at three to five times that rate due to deforestation, excess water use, and intensive farming. The alternatives – e.g. hydroponics – use more energy and resources to produce the same amount of food.

‘Beyond Politics’ – Rebels without applause

When metropolitan leftist politics disappears up its own press release.

There’s a new political party out there! At last! Just what we need in these troubled times! As lock-down was lifted ‘Beyond Politics’ was launched, “press release style”. Followed by a Guardian article covering their shoplifting of food from a Camden branch of Sainsbury’s to give to ‘the poor’ outside.

That was followed-up with a Facebook photo-post of them paint bombing the offices of Amnesty International and Christian Aid in pink paint, urging them to, “drive their organization into a final battle with the genocidal UK regime.”

A few days later, Extinction Rebellion issued a statement: “We also would like to be clear that Roger Hallam no longer has a formal role in XRUK.”

Well. That’s nice to know. Except that afterwards statements floated around that Hallam was still, ‘an advizer’. As is so often the case with Extinction Rebellion’s internal politics, most other (non-London-based) people were left to stand around texting, “WTF”.

Let’s be clear: London is not Britain. As British power politics is London-centric, that assumes not only that London represents Britain, but that ‘London’s problems’ are ‘Britain’s problems’. Go to East Lancashire, or West Devon, or Teeside, or the Black Country, and you’ll find a very different response.

If ‘Beyond Politics’ is a symbol of anything it’s as a living example of the David Rovics song, “I’m a Better Anarchist Than You” (find it on-line, you’ll get the idea). Change isn’t being radical for the cameras (that’s “mental masturbation”). Change is permanently improving the lives of people off-camera.

Let’s call this out for what it is: ‘Agent provaricators’ doing absolutely anything outrageous to get arrested is not a recipe for change. It’s just a stick to beat us all.

Environmentalism’s silence over ‘the limits to growth’ is an offence akin to climate denial

Why does the environmental movement complain about ‘climate change denial’ when they ignore the scientific research on the limits to economic growth?

In May 2018, ‘Deep Adaptation’, a paper by Prof. Jem Bendell, caused a stir in climate campaigns circles. It suggested that perhaps we’d gone too far; that instead of ‘stopping’ climate change perhaps we should adapt to the inevitable.

At the time, many who had been studying the issue of ecological limits, and the ‘Limits to Growth’, gave a collective yawn. Much of this has been discussed in research for over 45 years.

In July 2020 Bendell issued an update to the original paper. There are two significant admissions early on that we would call attention to:

- “I am new to the topic of societal collapse and wish to define it as an uneven ending of our normal modes of sustenance, shelter, security, pleasure, identity and meaning”; and

- “I explain how that perspective is marginalized within the professional environmental sector – and so invite you to consider the value of leaving mainstream views behind.”

In our view the second of those points actually answers his first observation.

Bendell is a professor of sustainability, whose career has straddled WWF, industry eco-organizations, and the UN. He is, by any sense of the word, a ‘mainstream environmentalist’.

Before the above, Bendell states,

“I briefly explain the paucity of research in management studies that considers or starts from societal collapse due to environmental catastrophe and give acknowledgement to the existing work in this field that many readers may consider relevant.”

In fact, what is most incredible about this new paper, like the original, is that it does not outline the best available studies on ‘collapse’. Most of his sources are ‘management’ studies for carbon emissions, not studies of ecological limits.

Though climate change campaigners have animatedly discussed Bendell’s paper, they still labour with a woeful ignorance of the history of the ‘science’ behind growth and collapse. Bendell doesn’t reference these works; they are perhaps ‘outside his field’ of primarily management-related research.

How do we reply to Bendell’s systematic failures? To begin at the beginning:

Many (neoliberal) economists call people who examine the ‘Limits to Growth’ hypothesis, ‘Malthusian’ – after Thomas Malthus, whose 1798 work, ‘An Essay on the Principle of Population’, first introduced the ‘ecological collapse’ of the human species.

Wrong; for the most ironic reason:

One of the first people to outline the idea that there must be ‘limits’ to economic growth was the founder of modern economics, Adam Smith (Chapter 9, Book I, ‘The Wealth of Nations’, 1776):

“In a country which had acquired that full complement of riches… which could, therefore, advance no further… both the wages of labour and the profits of stock would probably be very low. In a country fully peopled in proportion to what either its territory could maintain or its stock employ, the competition for employment would necessarily be so great as to reduce the wages of labour to what was barely sufficient.”

“It must always have been seen, more or less distinctly, by political economists, that the increase of wealth is not boundless: that at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the stationary state, that all progress in wealth is but a postponement of this, and that each step in advance is an approach to it.”

John Stuart Mill, ‘Principles of Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy’ (1865)

His ideological successor John Stuart Mill – founder of the discipline of ‘politics, philosophy, and economics’ (what ‘PPE’ meant before corona virus!) – also wrote on these issues (see the quote, right).

The Adam Smith Institute – the well-connected neoliberal think-tank that perpetuates the right-wing economic agenda in British political circles – deny that Smith or Mill understood what they were talking about. In their 2011 book, ‘The Condensed Wealth of Nations’, Eamonn Butler of the ASI states:

“Today we see no limit to economic growth. Our capital and technology give rise to all kinds of new business sectors and opportunities for employment. In Smith’s time, however, the economy was dominated by agriculture, and he mistakenly sees the impossibility of developing land beyond its fertility as a limit to economic growth.”

That simplistic rhetoric is infectious in policy circles. Recently a well-respected paper in The Lancet, projecting future world population growth, ignored ecological limits to population when it said,

“…food production is not a limit on fertility and population growth because food deficits can be solved by importing food.”

As the Free Range Network has promoted this research for the last 20 years, many of the responses we’ve had from ‘environmentalists’ have had a disturbing similarity to that statement.

Today’s eco-lobbyists have a messianic belief in technology as an ‘uncontested good’. They cannot see how the ‘industrial ecology’ of those systems creates the same ecological limits Smith outlined 250 years ago. Just as Jem Bendell’s view has been ensnared by neoliberal values, most of mainstream environmentalism now apes the ‘Cornucopian’ agenda of the economic right.

Mainstream economics abandoned physical limits in the 1930s. In response to The Great Depression economists began planning a concentration on ‘economic growth’: To give people more material wealth; and as a result, to create greater social cohesion and happiness as people lived more affluent lifestyles.

90 years later, that idea has been elevated to a ‘cult’ status by Western society – or more correctly, a ‘suicide cult’.

Alarm over the ecological impacts of technology and growth were raised in the 1950s; by researchers such as Lewis Mumford or Jacques Ellul, assessing the impacts of what was then called ‘technics’. Around this time dissenting economists – such as Karl Polanyi, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Kenneth Boulding – found new theoretical models to show the physical barriers to growth and technological development.

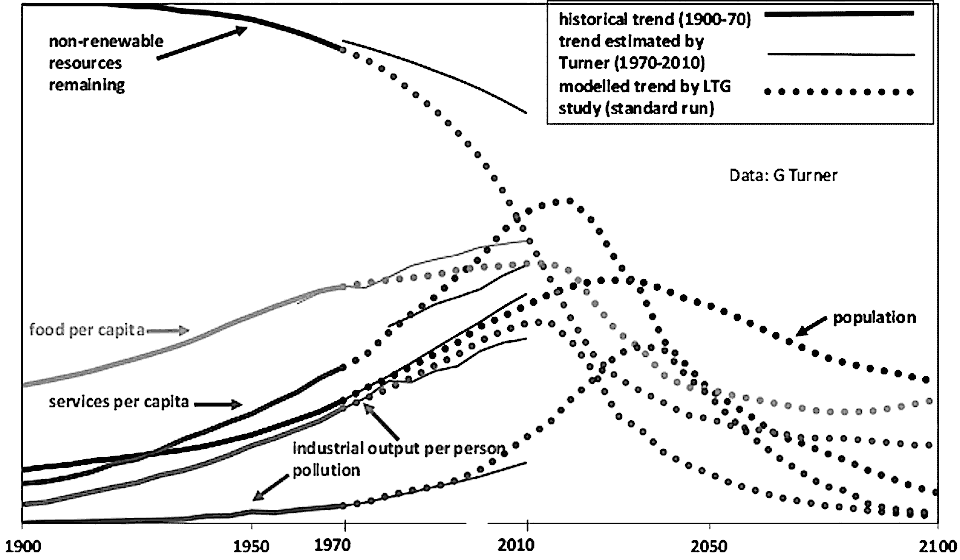

The most significant study to look at this issue was, ’The Limits to Growth’ (LtG), published in 1972. Based upon real-world data and using mathematical models, it predicted a collapse of the human system by the mid-21st Century as resources were exhausted.

It remains the most accurate long-term economic projection ever made.

The key message from LtG was that these trends are not linear. Growth creates an exponential increase in demand. As many ecological trends decline exponentially too, when these trends intersect the impacts become unsustainable very quickly, and collapse occurs.

Instead of challenging the data or the model, the opponents of LtG instead talked about ‘innovation’, ‘research’, and ‘new technologies’ that would push back ecological limits. This is what became the dominant message in the environment movement too – as it went ‘green’ and sought to become more ‘professional’ during the 1990s.

“Appropriate and publicly available global data covering 1970-2000 has been collected on the five main sub-systems simulated by the Limits to Growth (LtG) World3 model… As shown, the observed historical data for 1970-2000 most closely matches the simulated results of the LtG “standard run” scenario for almost all the outputs reported; this scenario results in global collapse before the middle of this century.”

Graham Turner, ‘A Comparison of the Limits To Growth With Thirty Years of Reality’ (2009)

LtG – despite updates from its authors published in 1992 & 2004 demonstrating its continued accuracy – languished in obscurity. Then in 2007/8 an Australian researcher, Dr. Graham Turner, working for CSIRO – the Australian federal government agency responsible for scientific research – revisited the ‘Limits to Growth’ hypothesis using the latest data. The core of his conclusions, published in 2009, are shown in the quote, right; the graph below shows his results.

Today climate change is already beginning to disrupt natural systems, and that is having an effect on society. Storms, flooding, wildfires, etc. Current projections indicate that the major impacts of climate change will not be felt until at least 2050, or more likely before 2100.

Recent research on the LtG hypothesis suggests that certain disruptions are happening today, due to peak oil, overfishing, or declining resources – major disruption is likely to set in from 2030 to 2040; well before the worst effects of climate change begin to bite hard.

As environmentalism will not revisit its roots in the debate over ecological limits, it cannot hold critical dialogue on technology and change – instead advocating ‘technofixes’ like green energy or electric cars without question.

Let’s consider that for a moment.

In June 2019 a panel convened by the Natural History Museum wrote to the Climate Change Committee, outlining their concerns about the amounts of minerals required to electrify road vehicles. As stated in their press release:

“To replace all UK-based vehicles today with electric vehicles, assuming they use the most resource-frugal NMC 811 batteries, would take 207,900 tonnes cobalt, 264,600 tonnes of lithium carbonate (LCE), at least 7,200 tonnes of neodymium and dysprosium, in addition to 2,362,500 tonnes copper. This represents, just under two times the total annual world cobalt production, nearly the entire world production of neodymium, three quarters the world’s lithium production and at least half of the world’s copper production during 2018. Even ensuring the annual supply of electric vehicles only, from 2035 as pledged, will require the UK to import the equivalent of the entire annual cobalt needs of Europe.”

There are one-and-a-quarter billion private and commercial vehicles used in the world; just 40 million, or 3%, are used in Britain… ‘Do the math!’

Any attempt to electrify society, while seeking to maintain the same physical ‘service’ provided by fossil fuels today, is blocked by similar physical barriers. All that will happen is the world’s richest consumers will gobble up the remaining resources, leaving nothing for the less affluent states to secure their transition from fossil fuels. From the viewpoint of ecological limits there is no reasonable compromise, as the idea of preserving the ‘affluence’ of 10% of the population does not serve everyone’s well-being.

Over the last fifteen years energy, economics, and resource research on ‘limits’ has turned up this same result: From Robert Ayres’ work on business cycles; to Charles Hall or Blake Alcott’s work on energy efficiency; Reiner Kümmel’s work on how economics is subject to thermodynamic restrictions; Ugo Bardi and Gavin Mudd’s work on minerals depletion; to Graham Turner’s continued work on the limits to growth.

In terms of what we might call “well-being”, another significant publication from 2009 was Wilkinson & Pickett’s book, ‘The Spirit Level’. It took data on global indicators of social development and plotted them against income inequalities. The results were as significant as ‘Limits to Growth’, and the book received vehement condemnation from right-wing economic lobbies as a result.

In particular, while rising incomes increase life expectancy, beyond a certain threshold it made little difference. And the level of that threshold? About $5,000/year (2005 prices). In other words, like expectancy in the most affluent states as not much better than those with a quarter or a fifth of those income levels – and in fact the additional consumption affluence brought created new social problems, as well as stressing ecological limits.

We now have a huge, multidisciplinary body of data on growth and ecological limits; and why ‘degrowth’, and the ending of extreme affluence and inequality are the only realistic response to current ecological trends. It appears Jem Bendell hasn’t read that data; and when it comes to advocating ‘doughnut’ or ‘circular’ economics, other figures such as Kate Raworth seem equally incapable of assimilating those messages too.

Ignorance of ecological limits cannot excuse advocating certain ‘solutions’ that cannot prevent continued ecological damage – especially where it simply perpetuates the lifestyles of the globally affluent 10% who cause much of that.

If environmentalist’s mouth the ideological dismissal of ecological limits originated by right-wing economic lobby, then that’s because those who ‘modernized’ the movement in the early 1990s wanted them to – to attract support from the centre-right of politics. Practically, though, that also makes their ignorance or denial of the limits to growth, and their imminent effects, as unjustifiable as the act of ‘climate denial’ practised by those same right-wing lobbies today.

“Nine meals from anarchy?” That’s not our kind of anarchy!

Enough criticism! What do we need to do? It’s time for activists to reclaim the deep ecological roots that inspired the environment movement, and create the resources and energy that supports humans, not machines.

In 1906, the American journalist Alfred Henry Lewis wrote that humanity is only, “nine meals from anarchy”. Others have used that as a metaphor for food security – when it means anything but.

Two things to note:

“Society can, if need be, do without prose and verse, music and painting, and the knowledge of the movements of the moon and stars; but it cannot live a single day without food and shelter.”

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, ‘What is Property?’ (1840)

Firstly we have to ask “whose civilization?” It’s not the peasant farmers of the world, or the hinterlands of small villages and towns they support – providing almost half the world’s food.

No, what he meant was the growing urban populations who are dependent upon long supply chains, bringing mass produced food into urban areas. That situation is worse today. A majority of people now live in urban areas, and food has been globalized – with ever-more complex supply chains. Bring a pandemic (or worse) into the frame and suddenly the shelves empty of toilet paper and pasta.

Secondly, that’s not our definition of ‘anarchy’. What Lewis describes as ‘anarchy’ is the failure of the mass market system of economics due to disruptions beyond its control.

“We accustom ourselves and our children to hypocrisy, to the practice of a double-faced morality. And since the brain is ill at ease among lies, we cheat ourselves with sophistry. Hypocrisy and sophistry become the second nature of the civilized man. But a society cannot live thus; it must return to truth or cease to exist.”

Peter Kropotkin, ‘The Conquest of Bread’ (1906)

Our idea of ‘anarchy’ is the complete opposite. What we advocate is people taking control of the essential elements of life – such as food and shelter. That provides greater security and resilience as, irrespective of the national or global “crisis of capitalism”, they will always have the wherewith all to support their basic needs locally.

For many that ‘solution’ is a tad too radical to think of; it attacks the modern, ‘convenient’ consumer lifestyle.

If the urbanized living system fails it is because we consciously accepted living that way – knowing of its flaws. Today, most of those flaws are keyed to the failure of technological systems as a result of ecological limits being breached. Thus the solution is very straightforward; perhaps so simple and boring that it’s positively not a sexy campaign idea to contemplate:

Remove the large-scale, inter-linked technologies from your daily lifestyle; re-establish a direct relationship between yourself and the land; once that’s done, everything else is negotiable.

Why is concentrating on access to food such an important part of planning a future within ecological limits?

Getting just the right amount of the right foods is the difference between a happy life, or ill-health and a slow death. Even in the worst of all world events, with enough good food you can sit together in the dark under a blanket and happily sing songs or tell stories; without enough food you get grumpy and start hitting people. It’s that simple. We don’t need more ‘big technology’; we need more local, self-created food.

Simple food, simply prepared, can reinvigorate the body and cheer the mind. Good food, well prepared, can restore a person who has been ill to better health. Even basic food, freely shared, can bring people together, heal grievances, and make an enjoyable event of any gathering.

This isn’t rocket science (unless by which you mean rocket stoves!).

There are three dimensions to this transition:

The first is ‘the personal’. It’s about learning to cook good, simple food, with basic simple ingredients, using the minimum of resources. Ideally you should learn to cook well outdoors. Why? Because when those ‘big’ grid-based systems fail you’ll be able to cook for yourself – and those around you – with a bit of practical improvization.

The second dimension is ‘communal‘ – creating a practical support network to meet local needs (A.K.A, ‘community’). One of the early drivers of ecological awareness in the 1970s was the idea of ‘self-sufficiency’ – producing all that you need yourself. That’s practically impossible (as many who tried discovered).

What we need to focus on is creating self-supporting communities; firstly as a few individuals scattered across an area, but ultimately with the goal of coming together for mutual support. That’s because everyone is good at something – and it’s that ‘mix’ of skills that make-up a functioning community. That’s been the unique strength of humans for at least the last 50,000 years.

Finally, we need to work on ’land rights‘ – a long overdue campaign in England (Scotland is way ahead of us already). The moment you try and create local support networks, the first thing you are confronted by is access to land: It’s difficult to affordably get it; and when you do, regulations prevent “eco-hippies” living low impact lifestyles upon it. In urban neighbourhoods, what communal land does exist is under the exclusive control of various local agencies.

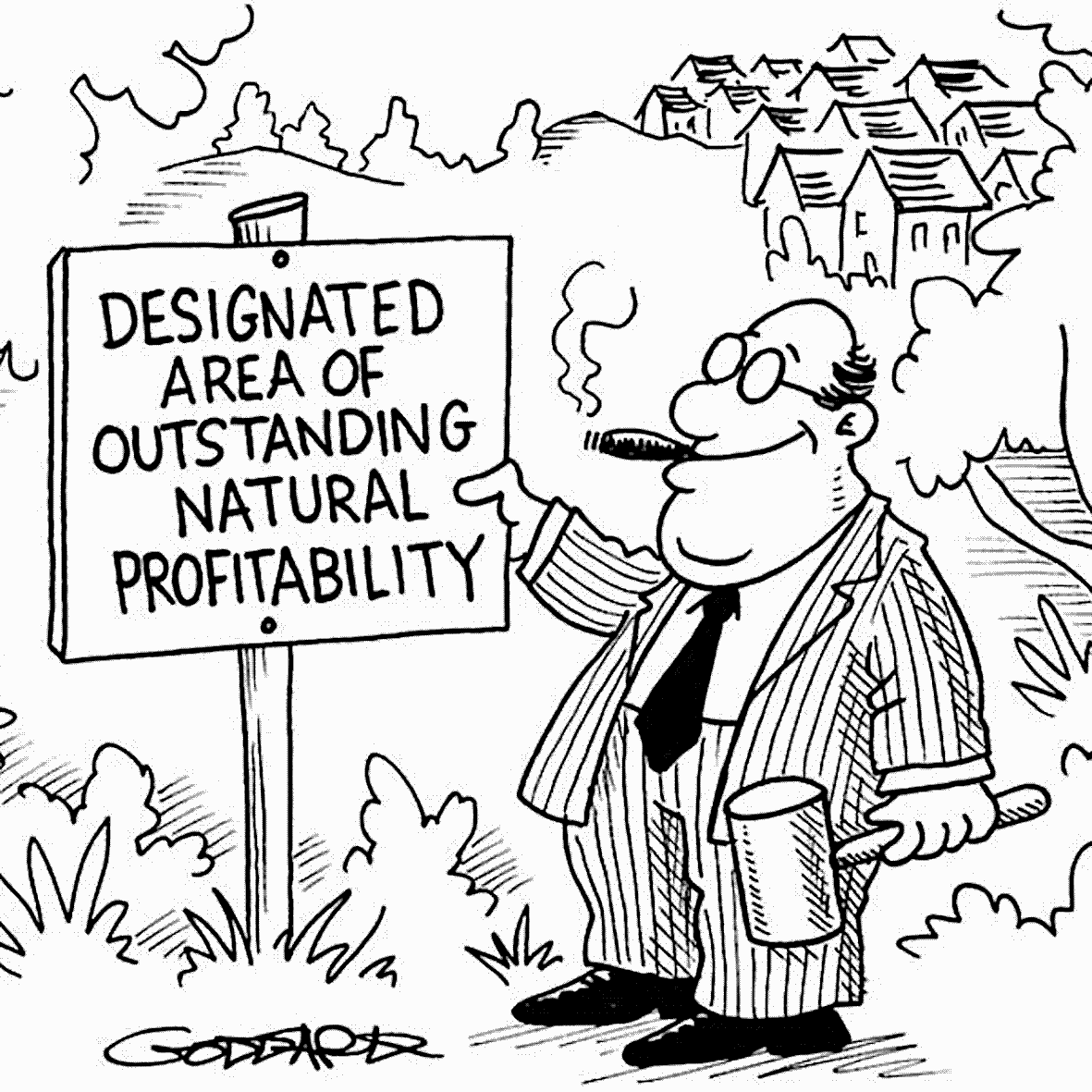

Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population – a third is still owned by the aristocracy, many of whom can trace that ownership back to Medieval times. That concentrated ownership – and more generally all proprietary property rights – are at the root of the destruction of our countryside and the entire world ecology.

The root of human instability isn’t just that the resources that make technology are running out. The industrialized consumer food system takes ten calories of energy to get a calorie of food into your mouth. Therein lies the true existential crisis. Any animal that expends more energy finding its food supply than it gets from eating its food will eventually die of starvation.

This isn’t just about big farms and agribusiness. From the planning system, to the way hedge funds operate, land is used as a tool to support unsustainable development (Boris‘ “Build Build Build” strategy is only the latest version of this practice). Breaking the elite’s monopoly on land in England is the first essential step.

We don’t need to “rewild nature” – a vision of large land-owners who want to promote a ‘neo-feudal’ green utopia. What we need to do is “rewild people within nature” by pressing for English land rights.

The only way we can significantly reduce the expenditure of energy and resources to feed humanity is to put them closer to the land – so they can work it themselves, with less resources, and close the resource cycles which are at the heart of a sustainable society.

Hang on! Isn’t intensive farming the most efficient?

No. Only in terms of capital economics, not the planet. Nor is this about ‘organic farming’ – which is just monoculture without chemicals. What we need is small-scale, human-tended, polyculture and permaculture foods systems.

If we keep the current system of a people-less countryside, and walled-in urban zones, how long do you think that delusion will keep working for? – once climate change and those other ecological limits kick in. It could collapse by 2030, but quite likely by 2040-2050. If that ‘crash’ is within your lifetime, when do you think you should start working toward achieving it?

The trouble with ‘consumer vegans’

Meat-free consumerism has no soul, nor any point.

All this talk of ‘food anarchism’ is very vague. As a practical example let’s think how ‘consumerism’ fails to solve critical ecological issues by looking at vegan food.

For us ‘holistic’ vegan types, who learned to be vegan before it was a mainstream thing, ‘consumer’ vegan food culture, purchased from supermarkets, is very confusing. If veganism is based solely on the principle that food doesn’t contain “dead animals” then arguably that’s a lie. From water pollution, to ocean dead zones, to climate change, intensive agriculture and food processing kills large numbers of animals in the pursuit of cheap food commodities.

The ‘unique selling proposition’ of ‘consumer’ veganism is that “it’s better than meat”. Absolutely true.

E.g., an analysis of a ⇒ ‘Big Mac’ showed that the 200g burger takes almost 2 kilos of inputs to produce it. Likewise it takes six times more calories of energy to produce than it delivers when you eat it.

To be realistic though, just because a product doesn’t enslave animals doesn’t mean it’s better for planet.

E.g., it takes lot of water to produce milk – cows need to drink, vehicles and dairies have to be washed, etc. Studies of almond milk have found it requires far more water to produce than dairy milk – perhaps 74 litres of water per litre. Commodity almond crops are often produced on irrigated land; that means robbing water from the natural environment – and wild species – to produce vegan food.

The difference between a ‘consumer’ compared to an ‘holistic’ vision of veganism are the conditions of purchase, and what choice or options you have in deciding those conditions: Consumer products come as a package – with everything decided for you in terms of sourcing and preparation. That’s it. If you want to vary the terms or the ingredients, bad luck.

By managing your own vegan diet, from basic ingredients, you can have infinite choice – but you also have to learn about food, nutrition, and how to prepare food cheaply and quickly; which takes physical & mental effort! The needs of living a holistic vegan diet requires you to be involved in planning how and what you eat, the conditions of its production, and how that meets your own values – which is also how an autonomous, self-guided (a.k.a ‘anarchist’) approach to lifestyle works! You could say, “Free your stomach and your life will follow!”

And there’s a big ecological and cost difference between the two:

- ‘Consumer’ vegan products come in small packages, made of printed card and/or plastic, made in large plants, using standardized bulk commodities from bulk agribusiness producers, all of which consumes a lot of energy and resources, generating a lot of waste.

- As ‘holistic’ vegans the tendency is to buy raw ingredients in bulk, to reduce cost. That reduces the amount of packing waste – and of course the processing energy and waste isn’t as great. Likewise, locally produced food, such as vegbox schemes, will often supply reusable containers – again, avoiding ‘single use’ waste. And when the shelves emptied at the start of the corona virus lock-down, how do you think us bulk-buying holistic lifestyle vegans fared?

- Finally, vegan products from supermarkets are often not priced by their cost of production; they are priced relative to the cost of an equivalent ‘meat’ product or ready-meal. You have a job to earn the cash to buy your food. That higher level of expenditure incurs a higher cost in terms of hours worked, and the wider ecological impact of your doing job.

Raw ingredients can be bought cheaply – often at a half to a quarter of the cost of buying those ingredients as ‘products’. As a result you don’t have to work as hard/as much to eat, and thus the impact is lower. Better still, if you had a small piece of land to grow them yourself, the cost would be minimal; in such a set-up you might not need to have a conventional, urban-style job to fund that.

The core of an anarchist lifestyle is embodied by holistic veganism. By taking control of our diet, preparing most of our needs ourself from simple ingredients, we can meet ecological ideals and global priorities. We can also have greater control over our economic status, and thus the autonomy that gives.

Numerical Ramblings – ‘Well I didn’t vote for him’

Why Britain’s electoral system is incapable of delivering a radical alternative to ‘business as usual’.

If Extinction Rebellion (XR) were not so single-minded in the pursuit of arrest over other tactics, perhaps they’d realize how non-radical their strategy was. Yes, that’s a lot to do with the technical debate – as other articles in this issue have covered. There is, however, a greater obstacle: Britain’s electoral system.

Very simply, XR’s tactic is to spawn mass arrests so the Government has to cave in and do something it doesn’t want to do. XR’s only hope is that a Government of sufficient enlightened self-interest is elected to heed these demands.

Is that an effective tactic? Let supporters take the financial damage while the state carries on regardless?

Sorry, we’ve a bit of bad news folks: Over the last couple of months analysis of the December 2019 election has begun trickling out. What’s interesting is the evidence for the level of anti-Corbyn bias exhibited by the media.

Research by Loughborough University showed that Labour had by far the most negative coverage in the national press. The Conservatives had the most favourable coverage. One key example was the critical IFS study of the party manifestos. IFS’ comments on the Labour’s manifesto were repeatedly quoted in the days after publication; the critical review of the Tory manifesto, barely at all.

Oh, the Greens and LibDems? They didn’t hardly get a look-in for media coverage.

OK, let’s assume that an “enlightened” party is able to negotiate its was past a barrage of negative media comment: The next barrier is the electorate.

When elections are discussed many cite the ‘unfair’ ‘first past the post’ (FPP) electoral system as the cause of our problems. Arguably that’s not exactly true – it’s more complex than that.

This diagram shows the votes cast at elections since 1970 (from Free Range poster, ‘The UK Democracy Chart’). Voter turnout collapsed in 1992. That’s not the Poll Tax cutting voters (they shrank more under Tony Bliar). People are just not minded to vote these days.

Bliar was highly critical of Corbyn, yet Corbyn polled more votes in 2017 and (almost) 2019 than Bliar did in two of his three victories. Bliar’s 1997 “landslide” was won off 31% of the electorate. In 2005 Bliar set a new UK record, since equal voting in 1928, when he won the election with just 21% of the electorate’s support – the lowest ever. Boris won in 2019 with just 29% of the electorate (44% of votes cast). The Greens only secured 1.8% of the electorate (2.7% of the votes cast)

This is a major obstacle. It’s not that ‘FPP’ produces disproportionate results. It’s that to get elected these days you barely need a third of the electorate. Until that’s solved, there will always be a bias towards ‘business as usual’.

Finally, exactly who sets the policy priorities for elections these days? If we look at the content of all party policies they are nearly always geared to middle class values. That instantly skews who will vote for which policies, and why.

In 2013, the ‘Great British Class Survey’ tried to estimate the make-up of British society. They found: 6% were a highly-paid ‘elite’; 31% were ‘middle class’; 15% were ‘new affluent workers’ (mostly self-employed trades); 14% ‘traditional working class’; 19% were ‘service sector’ with poor pay and contracts; and 15% were ‘the precariat’, who scored low in just about every way.

Analysis shows it’s the bottom 40-odd percent who are not voting. Most mainstream political policies in Britain – especially now Corbyn has been shown the door – arguably only benefit an affluent minority of all the electorate; and that in turn encourages only a certain slice of the electorate to vote. That’s a problem if XR want to create mass-appeal for truly radical ecological change.

Recent research by Aston University showed that XR’s supporters are mainly white, middle class, and highly educated. 85% had a degree – twice the national average – while a third had postgraduate qualifications. Do people like that get to meet and talk socially with members of ‘the precariat’? – unless they’re being served a sandwich on a street stall?

Recently XR organized a ‘Working Class Rebellion’ event. We queried how a panel of middle class campaigners could relate to working class perspectives on climate and the environment. The response? One reply said, “it’s a recruitment drive”; another, “they’re not talking about class, but about ways of organizing and mobilizing”.

XR are clearly qualified to do many things – but arguably that doesn’t include talking meaningfully to the less affluent majority of the electorate.

The issue is not simply that XR is painfully middle class – and hence white & affluent. The issue is that even if it were broadly-based, our national political debate would not reflect their point of view because it is currently incapable of doing so.

The best ‘new’ perspective that a radical organization can bring to UK politics is, very much, the position of punk in the 1970s: “just do it”.

Rather than get arrested on the streets of London, if XR wanted to make trouble it would create the radically alternative communities required to create a future sustainable society. Then, at the planning, or building, or operating stages it would challenge the law and be prosecuted or imprisoned, directly highlighting the practical faults in our state. At the very least it would be a move toward the solutions required.

The data suggests that just getting arrested to make change isn’t politically viable. We need to be ‘far more radical’ in our tactics than that!

W.E.I.R.D.: THINKING BEYOND TECHNOLOGY – No.2, Lammas 2020

A Free Range Activism Network Publication. Download other editions of ‘WEIRD’ at http://www.fraw.org.uk/frn/weird/index.shtml. Email any comments or feedback to weird☮frăwꞏörĝꞏuk. Issued under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA-4 license; you may freely distribute.